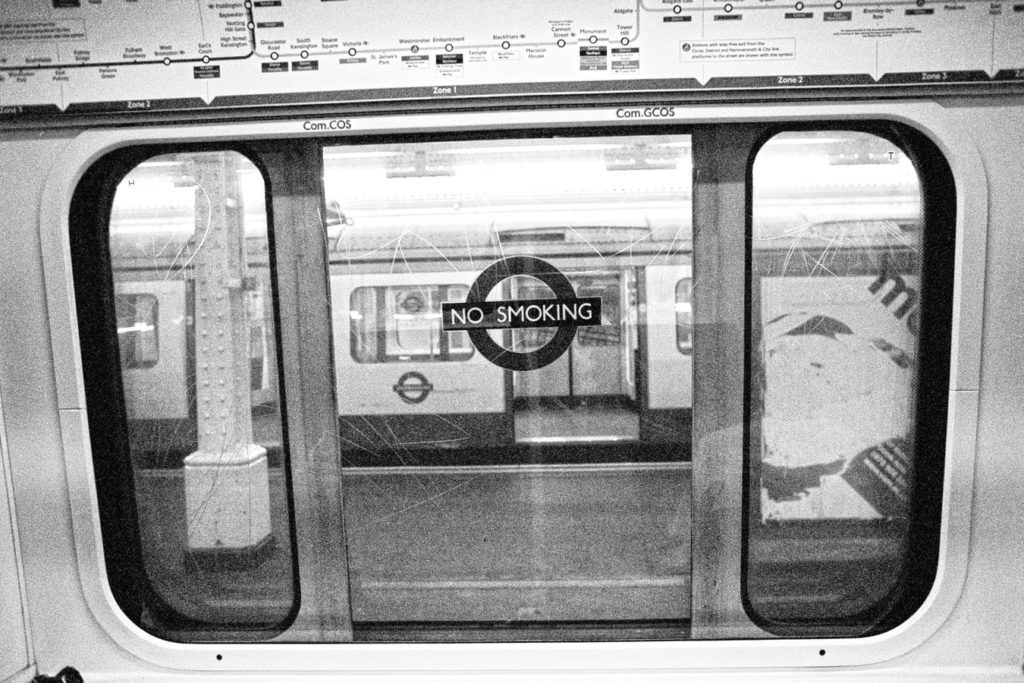

Each time the radio crackles I get a jolt. If it’s my callsign I pray it’s not the one type of incident I’m dreading. Abusive drunk, Miriam on Control says, all nasal with a cold. Relief lightens my stride through the underpass. The train’s still at the platform when I get there, all the doors open. Passengers glance up from staring at their feet or their phones, but no one speaks to me. It is my problem now: I have arrived to restore order to their lives. A suit who’s sat just inside the third carriage jabs a finger to his left, along the aisle, masking the gesture with the pink, folded pages of his FT. I straighten my belt and step inside. I don’t see anyone misbehaving, so my first thought is our miscreant must have gone, maybe tottering off down the tracks. Then there’s a shout, something drops with a thud and glass shatters. A man in a filthy, tattered raincoat strains to his feet and staggers through the connecting doors from the next carriage, slurring and spitting. He has a black can in a grimy fist, holding it out in front of him as if it is part of an act of worship. He misses a step and his coat falls open as he grabs at a handrail. I feel for my baton as I approach, but he turns his back on me. There are shrieks and feet shuffle and scuff to get out of the way as an amber jet hits the wooden floor of the District Line carriage.

‘Officer, are you going to just stand there?’

‘Jesus Christ, man. My shoes. My bloody shoes.’

He’s got his grubby, wrinkled cock in his hand and he’s twisting this way and that as he totters forward with the uncoordinated steps of a deep-sea diver, pissing all over their Oxfords and brogues and high heels and Chelsea boots. No one moves. The carriage deck soaks where it spatters, a dark spreading, foaming stain.

He clocks me and swings a right hander. It’s slow and it’s going to miss so I duck and get an elbow, shoving his weight forward. I get a nerve between thumb and forefinger and tweak it. The booze means it takes a few moments to register. I steer him down the aisle but he’s still pissing all over their shoes and trousers. I cuff his left wrist when we get on the platform and he lets me shove him onto a bench. He takes a last swig from his black can as I snap the cuff on his other wrist. Seeing the can seems to pacify him, so I set it down just out of reach on the platform. The fingers are trembling on my left hand: I grip them, squeezing and massaging till they stop. Effort, adrenaline, an audience I didn’t want, and his dead weight have drained me.

‘Took your time, didn’t you?’ A man in a tailored pinstripe, with the expensive haircut of a chat show host, looks down at me from the doorway of the train. He stands legs apart to avoid the spreading piss. ‘I’m sorry?’ he says when I don’t reply.

I shrug. ‘I didn’t say anything.’ I consider thanking him for his help but he’s the type to take my collar number and an hour out of his day to write a letter to the Chief. He’s got to be six foot four, has a winter suntan and works out, but before I got the cuffs on the filthy old vagrant he wasn’t feeling brave.

‘I said I’m talking to you, officer.’

I pat down the alky’s coat and find his pass. It’s issued by Camden Council and gives him free roam on public transport. The Tube is warm, and it goes round and round all day, a bit like a tumble dryer, so they’ll ride it for hours. His name is Arthur. I wonder what his story is. What was so bad he chose a black can and oblivion? ‘Arthur,’ I say, in a whisper, then louder. Not a flicker. His bald patch is filthy, and a wound is weeping at the crown, where he’s picked at a cornflake scab. It makes my skin itch to see it. He’s got dots on his knuckles and a Notts Forest badge crudely inked at the wrist. I mention Brian Clough but Arthur stares at me unblinking. He’s like a rescue dog: unsure of me, sizing me up and weighing me against past experiences with uniforms. He even tilts his head to listen like a Labrador I had as a kid. I get him on his feet and steer the cuffs, applying a few gentle turns so he keeps moving till we’re out of the station and back on the street. It takes twenty minutes for a van to show up and while we wait Arthur plays the martyr, hands cuffed, head down and stooping. A car toots at me and a bloke in a builder’s van winds down his window to tell me I ought to be catching burglars and rapists.

I’m new to the job, but it isn’t the first time I’ve heard this. Yeah, I’d like to be catching murderers, muggers, and rapists, but that doesn’t happen much for a PC. I see a lot of the same people every day and I can see they need help. I know they’ve fallen through the cracks and bad things have happened to them. I try to be kind, but I have a job to do and I can’t show weakness. Sometimes I must arrest them. Sometimes they get arrested because they want a blanket and a mattress and one of our curries. I wonder what Arthur wants. He stands as if he’s awaiting his own execution, rather than a sugary coffee and microwave chicken tikka. I don’t know what his arrest will achieve, but I put him in the cage in the back of the van and he slumps back, letting out a groan. Arthur is lodged with his powdery coffee (four sugars), while I’m sent to Gloucester Road to investigate reports of suspicious behaviour. Greasy hair, duffel coat, the only description. If duffel coat is being suspicious he’s gone to do it elsewhere, so I go walkabout and take the station’s emergency staircase, winding down the corkscrew of stairs deep beneath west London. Other than Tube workers and fellow Transport police, I rarely see a soul down here. It’s a welcome respite from being stared at or asked touristy questions. Twice today I’ve been asked to pose for pics: I must be on mantelpieces from Tokyo to Tacoma. I count the steps down in bouncy strides like a kid. At the bottom of the spiral staircase there’s a small pile of wallets. I nudge them with the toe of my boot. There are expensive leather ones, purses with zips, a gaudy polished crocodile skin and one with the maple leaf flag. They’ve all been filleted for any cash or cards, or anything that might ID thief or victim and tossed to the bowels of the Piccadilly Line.

If the pickpocket or ‘dip’, as we call them, was in a rush there may still be a tale in some of these wallets. There might be cracked photos of sweethearts inside, hopeful condoms long past their sell-by date, receipts for dry cleaning, or a child only seen on Sundays, pictured with an ice cream on a slide in the park. I don’t know the last time the stairwell was checked: there’s almost no chance of reuniting these wallets with their owners. They’ll go to lost property at Baker Street.

My radio goes off. One Under. My guts tighten. I close my eyes tight and pray. It’s Marylebone so it’s just off our patch. Thank God. I know my turn is coming and I don’t know how I’ll react. Instead, I’m sent to a beggar with child. Morning rush-hour has passed and it takes me twenty minutes to get there. The trains at South Ken are rammed so I have my photo taken with a Japanese man and his wife while I wait for the next one.

She’s sitting in the walkway. Some of them spot you in the convex mirror but she’s pale and weary and doesn’t seem bothered to move. She wears a pink tracksuit the colour of one of my nan’s old candlewick bedspreads. It’s black at the cuffs and there’s a tidemark of dirt at her wrist and neck. Her baby wears a romper suit with a hood that has ears like a panda’s. She stares at me with beautiful blue eyes and I realise she’s pointing at the shiny badge on the helmet. I take it off and she runs her fingers over it. ‘You can’t be here,’ I tell her mother. ‘It’s no place to bring a kid.’ She’s not listening to me. She likely thinks I’m no more than a kid. She has no ID. The name she gives, but I don’t bother to write down, could belong to any of a dozen Traveller families. I wait for her to make her way up the steps. She’s careful about gathering her things tight about her, which means the coins must be in her woolly hat or her scarf or her bag of baby things. I’m not fussed to take a half kilo of dirty copper coins. I watch her trudge up the steps as my callsign is given.

My stomach knots. I shift my belt where its pressed into the small of my back, striping my skin. I’m told a Swiss tourist is upstairs in the booking hall. A man has exposed himself to her on a train. She’s been given coffee and clasps the mug tight. She hasn’t seen his…..she searches for the right word and the woman scanning the CCTV says ‘meat and two veg, petal’ without turning from the screen. It might be a man we’ve been after for months. I take a statement and her contact details, and the station supervisor offers her a taxi home, but she prefers to walk. ‘I didn’t see anything, you know,’ she says. ‘Well, it’s cold out, so maybe there was nothing worth seeing,’ the CCTV woman replies.

II

I’m back at the station when the radio crackles. A man is on the tracks at Royal Oak. Seven minutes in the car, trying not to grip the arm rest. I’m out first, tugging on gloves as I run. ‘He’s out there now. You need to move him,’ the station manager stammers. I offer up a silent prayer he’s alive and not my first one under. I walk to the edge of the platform and see Michael lying in the gap between the tracks like Penelope Pitstop. He is well known to us. ‘Get up, Michael. For fuck’s sake.’ He doesn’t move, except for a little shimmy on the oily sleepers, as if he’s shuffling to find a comfy and cool spot in cotton sheets.

‘We’ve had to stop the trains.’ He closes his eyes and rests his hands on his belly. ‘Funny spot for sunbathing,’ I tell him. ‘Come on, Michael. You’re not going to kill yourself.’ I sit on a bench waiting. After two or three minutes, Michael gives up and I help him up to the platform. We’re forced to wait in A&E until someone can come down. It’s boiling hot and manic and we take our places on plastic school chairs next to drug addicts and drinkers and a kid hit by a taxi and a woman missing a finger and a guy with a split cheek and an eyeball that’s swollen up like a ballcock. We might be seventh, eighth in line if we’re lucky. Stan tries working the coffee machine, while I go for a wander. ‘Not that way,’ he says. I kick back, crossing my feet. ‘What’s through there?’ I say.

‘No, you don’t want to go through there.’

I sit with Michael. He says nothing, sitting unblinking beside me for two hours. He accepts a hot chocolate from the machine. It’s all I can usefully do for him.

III

I reach for a towel, eyes stinging with tea tree shower gel, and I hear the call signs on the radios competing, boots clattering the lino and doors slamming.

‘Get dressed. We go in five.’ I can’t see him, but I know the sarge’s voice. I dry off as hastily as I can and hop on one foot, tugging on my boots. Down the stairs and I’m in the van as they hit the lights and sirens. We swing out into the traffic when I realise my back is still damp. I don’t want to ask what’s going on. The radio traffic is non-stop, callsign after callsign getting sent across London.

‘Train crash,’ Eddie says. ‘You got a coat?’

A helicopter buzzes overhead, news crews sweeping the site. Diesel pricks my nostrils, an acrid burning. I duck through a gap in the railings and follow a track through wasteland. Through a gap in the weeds and brambles I see a train carriage lying at an angle, over on its side. A pall of grey-black smoke drifts over the semi-detached houses lining the track. Fire crews are shouting to each other. There are men everywhere, wearing orange safety vests, pointing and beckoning to others. Fire crews sprint to the site with kit. A woman who is holding a bandage to her head is led away by paramedics.

A sergeant scrawls 167A on a yellow sticker and slaps it on my chest. ‘Inner cordon. Don’t move till you’re told to,’ he says. Swivelling away from the crash site, I slip in the ballast, grateful my boots prevent me going over on my ankle. After glancing this way and that in search of somewhere I’m needed, I notice three other police constables I don’t recognise strolling determinedly to a point where the fire brigade has set up a cordon and decide to catch up with them. ‘There’s bodies through there,’ one of the constables indicates to his left. I try not to look, but I can’t help it. A suited man lies in the ballast. He’s on his back but a pile of suitcases and bags obscures his head. A watch commander is ordering a firefighter under a jacked-up carriage. Another body – I can’t tell if it is that of a man or woman – lies face down, surrounded by bags and cases. I swallow. Phones begin ringing. I get told to get my hands out of my pockets. An inspector points up at the sky. ‘See, you’re on TV, lads. Now, get bagging that stuff up.’

Firefighters are handing us stuff. I realise it has happened. Not just one death though, but several. ‘You OK?’ a sergeant says. I nod too quickly. ‘Keep busy. It helps.’ We take property bags and scrawl numbers and times on them. Property is being brought out in armfuls and dropped onto blankets. I’m glad to have routine, mundane tasks in the middle of all this. Eddie was right about needing a coat. It’s got colder and I start to shiver, arms goose-pimpled. I’m picking up phones, wallets, lunchboxes, pens. A phone rings as I drop it in an evidence bag. I glance at another PC and he shakes his head. He works at Victoria and only has a few more months in service than I do. A firefighter shouts. It breaks the silence and I carry on bagging property and possessions from the carriage. We’ve filled dozens of bags at the trackside. I’m cold and hungry but there’s no way I’m going to complain.

Later, someone heading east drops me back at Earl’s Court. I don’t remember anything about the journey, except my skin, cold against the glass of the passenger window. Whoever is driving says nothing, but that’s not unusual among cops. I’m exhausted but wired with adrenaline and my feet jig in the footwell. I phone my girlfriend. I can’t handle exchanging war stories at the police section house. Instead, I get the Northern Line to her flat, where she makes me a strong builder’s tea. Whisky is what I need. I sit and say nothing and feel bad. Take your time, I think she says. It’s hard to hear her: the phones continue to ring in my head, the phones of people who had gone out that morning but wouldn’t return.

Richard Lakin is a former police officer, journalist, editor and labourer who graduated in chemistry. He lives in Staffordshire in England with his wife and sons and dog. His work has been published in numerous magazines and newspapers and he has won annual travel writing prizes in the Guardian and Telegraph newspapers.