It’s a very long time since I got the binoculars out and spotted a plane, but I still dream about them. Often. Not quite a recurring nightmare, but a recurring theme – planes crashing. Usually I’m back at my mother’s house, which I left forty years ago, and where I first started looking up at them. The earliest dream I can remember was about planes – sort of. I imagined I was awake and outside very early on a summer morning, hours before anyone got up but still light. I saw something overhead which looked like a hovercraft. Later I found out hovercraft couldn’t fly thousands of feet up. Still, that didn’t dampen my conviction in what I thought I’d seen; I refused to believe it was a dream, though I suppose it must have been. And I had to admit, I did have a track record. I was a sickly child and often in a high fever, to the point where I’d hallucinate. Don’t laugh, but I used to imagine Tich and Quackers were living behind the headboard on my bed. Tich and Quackers were Roy Allen, the TV ventriloquist, and his dummy, so in all probability they weren’t living behind my headboard. But for quite a while I was very scared about going to bed.

I’m less confused now; when I have a dream, I know it’s a dream. My last recent plane crash nightmare was very vivid. There was a four-engined British Airways jet – not a real aircraft, some amalgamation of an Airbus and a jumbo, and it was pointing down at an improbable angle, and far too low. That’s a common pattern in the dreams; the planes are always wrong – wrong altitude, wrong attitude. I’ve watched thousands of planes from the roof terrace at my mother’s, and in an easterly wind they all approach Heathrow the same way. (In a westerly wind they take off over the house and are too high to catch by the time they pass over the house.) Landing, they make a gentle loop onto finals, then slide down across Windsor Great Park and over the castle. It’s round about here where the dream planes go rogue.

The last one was just a few hundred meters away from the house, far too close to the fields behind, pointed towards the earth. Sure enough, it went down, the point of impact hidden behind a dreamt up tower block, part of the expanding new town nearby; true, the town is spreading across the Green Belt, but only at such a rate in my dreams. There was a moment’s peace before the fireball, then the smoke erupted over the building, and the boom shook its windows. The nightmare landscape around my mother’s house must be littered with the broken fuselages from all these dreams. This time was worse than usual; I was out in the open, but there was no time to make a futile run towards the plane before the block of flats tumbled down, over the house. My mother miraculously survived, but in what seemed like only hours the police (I was glad to see they were still functioning in this post-apocalyptic dream world) had walled off her home. Despite their efforts, I could see through a gap in the brick to people looting the rooms, shredding the tissue of my inheritance.

Like the broken planes of my dreams, LXX Lincoln International Airport doesn’t really exist. I made up the IATA code, which doesn’t relate to any real airfield; Lincoln is the name given to the eponymous airport in Arthur Hailey’s novel, the first disaster blockbuster. The novel reflected the glamour of modern air travel, but also the terror of it; why wouldn’t one of these metal tubes just fall out of the sky, especially on a stormy, snowy night? My own nightmares illustrate these deep fears we have about planes and flying; even me, someone who loves the bloody things and loves flying in them and has done so hundreds of times. Why are we so scared?

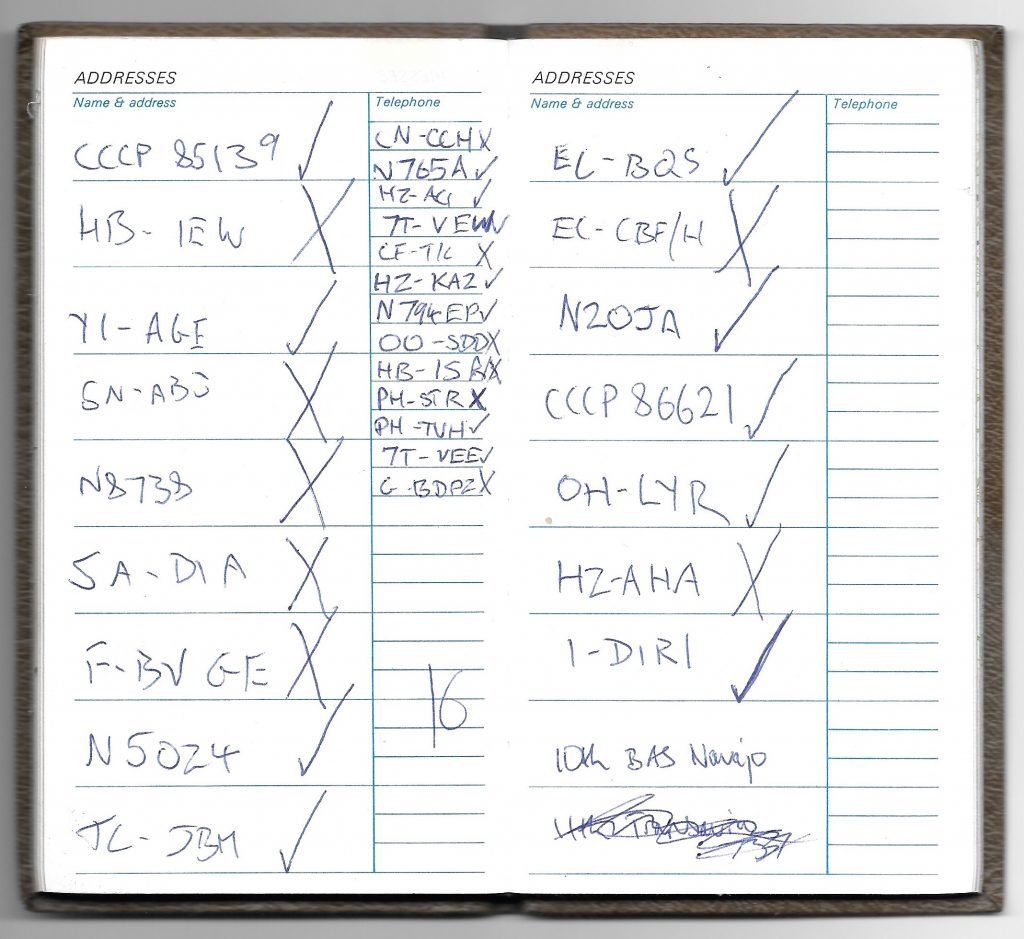

Planes do crash, of course. There’s a piece of ‘raw data’ I still have, a list of spotted plane numbers written on the blank pages of an unused old diary. From the traffic recorded, I would say they were the haul from a day’s work at Heathrow. There are twenty-two numbers on the left-hand page; of those twenty-two, two have crashed.

5A-DIA, a Libyan Arab Airlines B.727 with all three jet engines crowded around the tail, was nearly eighteen years old when it was lost, but the accident was nothing to do with the aircraft’s age. It crashed into a Libyan Air Force Russian-built Mig fighter on approach to Tripoli airport, and all 157 on board were killed, as well as the two occupants of the Mig.

(HB-IEW was a Grumman Gulfstream II business jet, a forerunner of the 1986 Gulfstream III my father used for a few very expensive years in the 2000s. )

7T-VEE meanwhile was another Boeing, a twin-engine 737 registered to Air Algerie, and would have been in that airline’s colours when I spotted it at Heathrow back in the 70s. It was being operated by a Dutch-based freight company Phoenix Aviation when it crashed coming in to land at Coventry just before Christmas in 1994. Much attention was paid to this accident at the time, being one of the worst to happen in the UK, and with the added contentious factor that the plane was carrying live animal cargo. There was a sequence of factors which caused the accident. This aircraft was even older than the Libyan 727, with twenty-one years’ service, and while there was no suggestion of mechanical failure, it didn’t have the most up-to-date navigational systems, and couldn’t cope with deteriorating visibility at Coventry-Baginton. At first the plane diverted to East Midlands Airport, but as the weather supposedly cleared during the morning, another attempt was made shortly before ten o’clock. However, the visibility was still poor with the cloud level at only 600 feet. Compounding this, there was a misunderstanding between the control tower and the cockpit, and the plane approached off course and too low, the left wing hitting a 300 foot high electricity pylon just a mile from the runway. The plane then pitched and the same wing struck the roof of a house, cartwheeling into woods with the loss of all five people on board; there’s no mention of the fate of the animal cargo in the accident reports. It transpired that the crew had been flying all night, making five flights with six approaches shuttling cattle from Amsterdam to Coventry. including the aborted one into Coventry in the early hours; their fatigue would probably have been a factor in the tragedy.

Still, as they’re always telling you, air travel is one of the safest modes of travel. Certainly true if you measure it in terms of fatalities per kilometre travelled: 0.05 deaths per billion on a plane compared with 3.1 per billion in a car. Which is why an awful lot of planes fly for thirty or forty years and don’t crash. So what happens to them? Well, they end up in a graveyard. Or a boneyard, as they call them in aviation circles. We visited one once when we were on one of our US holidays, Mojave Air and Space Port. A trip to Disneyland which we subverted to our plane habit, Jumbo over Dumbo. Rows and rows of airplane husks neatly lined up in the desert.

Aircraft seem to be one of those things which humans don’t know what to do with when they’re finished, like plastic bottles. Or nuclear waste. At the end of their serviceable lives, planes get flown to these wastelands and then parked up in their thousands, ostensibly in a preserving environment where in theory some of their parts might still be utilised. In reality the carrion lies there interminably, the aircraft bones never rotting in the hot sun.

The largest boneyard is at Davis Monthan Airbase in Arizona (which incidentally boasts a high incidence of UFO sightings,), and this houses over 4,000 wrecks, although most of those are military aircraft rather than airliners. The one we visited, Mojave, is home to a thousand airliners, and between them the aircraft graveyards of the West Coast states house tens of thousands of planes.

So if air travel’s so safe, and all these planes enjoy a peaceful retirement in the desert after flying for decades without ever crashing, why do people get so scared?

There is of course the terrorist incident that can never be ignored or forgotten. The images of AA11 and UA175 puncturing the Twin Towers are seared on everyone’s consciousness, images so extreme that they contort into nightmares at the very edge of credibility, exaggerating our fear of flying and ever ready to flare up in our imagination. I do wonder if my own horrible plane dreams would have been so frequent and so vivid if September 11th 2001 had passed as uneventfully as every other day.

I was due to fly from Newcastle to Dusseldorf for a trade fair on September 12th 2001. There were a few of us going – I was boss, but the whole buying team were on the trip. I gave people the choice as to whether they came or not, and everyone did: permablonde Vikki who probably had more pairs of shoes at home than we did in one of our shops; short and serious Misha who did the numbers, i.e told Vikki how many pairs to buy; and their boss, my fellow director but subordinate Andy, a practical joker who we’d usually expect have a fart cushion stored in his carry-on baggage ready to install on an airline seat. . Perhaps not today, though it was still a major effort to stop him making jokes about bombs as we shuffled through passport control and an unsurprisingly rigorous luggage check, the usual airport hubbub muted by apprehension He couldn’t avoid asking me in front of the customs officer ruffling through my underwear whether I’d brought any porn mags with me.

Nothing happened, of course. And the truth is, it very seldom does – since 9/11, the American translation we’ve been compelled to adopt, not a single British life has been lost in a terrorist attack on aviation. The only time I’ve ever been in real danger in the air was when my own father was the pilot . Not content with embarrassing me in front of my classmates with white Rolls Royces and pink Cadillacs, my father came to collect me one day from school in a chopper, landing on the football pitch.

It was a small helicopter, more a tangle of glass and tubes than an integrated machine. No sooner had we taken off than we disappeared into a mass of low cloud. My father was no expert pilot; he’d only just got his licence and this was his maiden solo flight. He had no experience of instrument flying; he flew by visual flight rules, and therefore was totally dependent on what his eyes could see, or in this case, both our eyes. The cloud ceiling was around 500 feet, barely higher than the electricity pylons puncturing the Berkshire countryside. All he could do was use the compass to head east, flirting with the base of the cloud while praying that he was above the wires and turrets, and able to react in time to any sudden rise in the terrain. I had instructions: to watch out for these hazards, for any other craft also foolish enough to fly in the conditions, and for any landmark that might help to guide us. If I saw anything I had to shout at him over the crackly intercom, the cockpit being too noisy for us to hear each other naturally, despite being only inches apart.

He flew as slowly as he could without stalling the helicopter, a very basic Bell 47, with just our two seats surrounded by a glass bubble. Nothing familiar below, just field after field, lane after lane, the occasional rise or communications mast to swerve around. Then a miracle; we passed over a runway, the husks of three ancient helicopters ominously lined up at one end. Not daring to keep heading towards home, we set down on the grass to the side of the tarmac. More by luck than judgement, my father managed to make contact with the control tower over the airband radio; it turned out we’d come down at Blackbushe airport – at the wrong end of the runway away from the tower and terminal. He’d used another of his nine lives. I hope I get as many.

I’m not flying any more. Nobody is. My first trip to London since lockdown and I’m at a steering wheel not a joystick; there’s more solid steel around me in my hybrid SUV than there was in that flimsy helicopter. As I approach from the South, everyone else is heading out of town, to enjoy the tropical weather. I hadn’t realised I was going to hit Croydon, a small American city plonked down in South London, and the home to London Airport before it moved to Heathrow. I weave through the under- and over-passes, an extra in a Philip K. Dick novel as the low sun flashes off the skyscrapers in the thirty degree flame sky. There’s no flight trails to carve it up. It would be so easy at the top of one of these urban rollercoasters to flip the wheel, and launch into the air, the car becoming a plane itself for just one moment, before creating its own tangled mess of metal and bone below.

Mark Blackburn is an ex shoe retailer, now writer of fiction, memoir and children’s books. He has been shortlisted for both the Fish Short Memoir Prize and the Fish Lockdown Writing Prize. LXX forms part of his current work-in-progress, Final Approach: My Book of Airports, a subjective critique of real airports around the world. You can find more of his work on his website. @markblackburn

Cover art by Ladina Clément.