I am eight years old and waiting outside a betting shop in Kentish Town for my father to come out. When he eventually steps out onto the street, at last responding to the message I’ve delivered to him from my mother, he is a whirlwind of sweat and smoke, as if he were pissed drunk (my father didn’t drink, and from the age of eighteen was a ‘pioneer’; a fact he will hold up his whole life as evidence that he is not an addict). He’s utterly unfocused on me, or on anything around him, and I know immediately he’s lost all our money; the money that my mother has sent me to stop him gambling. We eventually lock eyes: he knows I know. This is my first experience (which is mostly like a smell) of abject desperation – and I am shocked by it, hence, no doubt, my vivid memory of this moment. It is also one of my earliest memories of daily life in London.

∆

In the UK census of 2001, close to 700,000 people claimed to have been born in Ireland, 12.1% of the population of Ireland at that time. In the UK census of 2011, a smaller figure, around 450,000, claimed to have been Irish-born, though in the same year, probably due to the banking crisis and subsequent recession, emigration from Ireland to the UK rose by 25%. In 2018 the amount of Irish-born people in the UK fell again, to less than 400,000, the average age of this group being 53. But what of the second-generation Irish? Kevin Kenny, Professor of History at Boston College and author of Diaspora: A Very Short Introduction, states that ‘70 million people worldwide claim Irish descent.’ Certainly, if the recent rush in the UK to get Irish passports is anything to go by, the figure for non Ireland-born Irish is pretty high, with the highest concentration most likely to be in London. According to the UK think-tank The Runnymede Trust, there are 6 million second-generation Irish people in Britain, around 11% of the population and more than the population of Ireland itself.

Hence, in terms of emigration, there would seem to be a peculiar supply and demand relationship between the UK and Ireland, one that is dependent on socio-economic and political factors in both countries; people have been emigrating from Ireland to England since the Norman Invasions and probably before. And while it seems that with each wave of emigration – before, during and after the Famine, post-Independence, during recession – there are different sets of circumstances, with the emigration of increasingly skilled people from one wave to the next, the result is the same: replacement of the previous life and culture with a new life and culture. In terms of cultural identity, this change often establishes in the emigrant/immigrant the trace of a fracture, and if you are the children of these emigrants, as I am, the fracture becomes more defined: being both from our parents’ birthplace and our own, we can often feel like we belong to neither. This wavering sense of belonging is where the fracture is found.

∆

When people ask me where I’m from I sometimes jokingly reply that I was conceived in Golders Green and born in West Hampstead, on Narcissus Road to be precise, and that it was all downhill from there (Narcissus Road is on a steep hill). From Narcissus Road my parents moved to Quex Road in Kilburn, where they lived for eight years in a spacious but dark basement flat in which they had three more children. Our family of six moved then to the Queen’s Crescent area of Camden (in Northwest London), into a five-storey block of flats called Penshurst, behind which is Drama Centre, the famed drama school. My father, a complicated character from a well-to-do family in Sligo, who, despite spending his days at the races or in betting shops was something of a snob, was none too pleased to be setting up life in a council flat (no doubt judging this, wrongly, as further evidence of his failure in London), but after eight years in the basement flat in Kilburn, with no sign that we were ever going to move into something brighter and bigger (or that he was ever going to quit gambling), I doubt we had much choice. We moved in (my father absenting himself from the actual day of removals due to the ‘trauma’ of it, he later claimed) to number 56, on the second floor. My mother promptly changed our schools and became involved with the local church, St. Dominic’s, in Gospel Oak.

There was a group that assembled after mass in St. Dominic’s called Pax Christie, and my parents joined them. The ethos behind this Catholic ‘reconciliation movement’ is that there is no hierarchy between lay people and clergy, and so even to my child’s mind they seemed wildly progressive. In a well-furnished room at the back of St. Dominic’s, Pax Christie members would sit around drinking tea, chatting animatedly about the mass and indeed, politics. To this day I can recall the strong sense of camaraderie in that room. It was all made possible by St. Dominic’s resident priest, Father, or as he was sometimes more officially known, Monsignor, Bruce Kent.

Bruce Kent was, and remains (at the time of writing he’s still alive and politically active) a compelling presence. I especially remember his homilies, mainly because he did something I’d not seen before – nor since. He would ask attendees of his mass for their opinions on the homily he’d just given, or on the politics of the day, and many would stand up and give them. The mass regularly became, then, a vibrant discussion, which would continue afterwards at the Pax Christie meetings.

Kent brought out something more constant in my parents, too. For their lives at this time were erratic; my father’s gambling had gotten out of hand, my mother was recovering from breast cancer (contracted at 34) and my brother had a rare and difficult-to-treat heart condition (for which he’d undergone several operations in Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital). There was zero financial stability, and the regularly posited solution to this was ‘returning to Ireland’ (familiar, I’m sure, to many Irish families living abroad as a much-heralded salve to all problems), which my mother, at least prior to moving to Queen’s Crescent and meeting Bruce Kent, wanted to do desperately.

This modern priest at St Dominic’s, who’d welcomed my parents and helped them settle into their new community, and who found in my father a fellow Left-leaning type, was, whether he knew it or not, a guiding light for my family, a lone beacon in London. One Sunday, the subject of Kent’s homily was Vietnam. So inspired were my parents – and I – by his anti-war fervour (and the discussion that took place subsequently at the Pax Christie meeting) that I wrote a poem:

The War, the War, the War must end

for Vietnam is round the bend.

Look at the people, hungry with starvation

and that will go throughout the nation.

God the master gave the Dove

to Vietnam to bring back Love;

I hope Vietnam returns to peace

and this dreadful War will one day cease.

My mother showed Bruce Kent this poem, and shortly afterwards he visited us at our Penshurst flat. He was full of thanks and praise for its eight-year-old author. Of course, he will never know that the praise he bestowed upon me that day bolstered my confidence immeasurably, and that from that moment on I wanted to write.

We continued to attend Kent’s mesmerising masses every Sunday for the next few years. But just before my mother inherited the house in Ireland that would change all our lives, Dad came into the flat, downcast. ‘They’re excommunicating him, the bastards,’ he said. Kent had been a supporter of CND and the Greenham Common Protest, and though in actuality he was not excommunicated but later left the Church himself rather than comply with its request to desist from politics, it more or less amounted to the same thing.

INHERITANCE

The difference between London and Ireland – border-town Ireland to be precise – in the late-1970s, was the difference between day and night. My mother’s inherited house was in Dundalk, and though the town had the BBC, unlike many other parts of Ireland at that time, the first few weeks living there felt as if I’d stepped back in time, to the 1940s or some similarly Spartan era. It was a complete contrast to the colourful punk scene I’d been a witness to in London before we left. The priests of our local parish wore long black frocks, carried canes and walked with a well-honed arrogance, as if they aimed to terrify. I felt very keenly the contrast between the two places, and could palpably feel the conservatism of the church in the country we’d just moved to. Ultimately, this seems to have suited headquarters in Rome far more than the discursive and open-minded (and English) Catholicism of Bruce Kent.

The first year of the move to Ireland was without my father. I missed him terribly. The deal was: he would stay in London to work and send my mother money while she set up home in Dundalk. (No such money ever arrived.) I’m guessing that it was also a kind of test to see if Ireland was a place to move back to without first giving up the flat in London.

My mother seemed to find a new freedom in her inherited house. Finally, she didn’t have to worry about rent, and if the electricity was cut off due to power cuts or non-payment of bills, which it regularly was, she still had a roof over her and her children’s heads. The house, a redbrick terraced townhouse that had been in my mother’s family for over a hundred years, was a veritable museum: dark and unmodernised, full of dusty antiques, and though I protested in every way, at twelve years of age I was going nowhere else. She began to plant flowers in the small back garden, grew tomatoes. I observed her gain some control and mastery over her new space, and of her life; in London she had seemed always so pensive. The Dundalk house had no bathroom however, and in our first years living in it we would bathe at the kitchen sink or in a tin bath. Going to the outdoor loo at night was an experience in itself, usually with a candle or torch. Initially, my parents had planned to sell this house and move to Dublin, where my mother was from, but, as with my father’s promises to send us money from London, these plans came to nothing.

Dundalk at this time, and until the 1990s at least, was a bleak, in parts brutal, industrial town. The only way to see some genuine rurality was if you had a car (North to the Cooley Mountains or Carlingford, West to Monaghan). And we didn’t have a car. The nearest easy-to-get-to-without-a-car beauty spot in the Dundalk area is Blackrock, a coastal village three miles outside the town, to which we would walk in summer or take the bus. And later, I would cycle there with my new-found friends, or siblings.

But Dundalk itself was not at all beautiful. It was grey and everything about it was grey. A walk along the back of the town, along the Ramparts River, was a study in all shades of grey. There was even a Greyhound Stadium, to which my father made a bee-line the moment he (eventually) returned to his family. There were many dilapidated buildings here, a few factories, and the river itself was thick with sludge and rubbish. The first time I ever saw rats grouped together was in that river and they were immense in size. The place – and our lives – sound Dickensian, but this was the late-1970s. And, being a border town, Dundalk was also deep in the Troubles. British helicopters were a common sight as they raced across the skies making regular incursions into Irish airspace; people were bitter, aloof, suspicious. There were few supermarkets, and the smaller grocery shops were archaic. In one, Wards on Park Street, the cheese was cut with a wire by a large-boned, almost mute woman with a Louise Brooks hairstyle, who passed the money along on a string to a separate cash area. ‘English?’ she would occasionally ask me or my siblings, as if this particular question was the only thing worth breaking her silence for. Life here, at first, was a shock to my system, and it took a while for me to settle into this new environment.

∆

My father opens a betting shop in Castlebellingham, a few miles outside Dundalk. We’ve been in Ireland a year and he hasn’t been able to find work, so this is his plan to make money. (It is widely accepted that publicans who drink do not make good publicans. The same goes for gamblers; they do not make good bookies.) I go with him on the morning bus to the one-room shop he has rented on the main street of the village. Now aged thirteen, I am his more or less unpaid ‘settler’. I settle bets, calculate winnings and mark the bets up. In a few days, word gets out and the shop is busy. It feels good to see my father take pride in his new venture and I love being in his company. Though a few weeks later, there is suddenly a familiar smell in the air: that chronic desperation again. A punter has won big on some race and we do not have the funds to pay him. Not long after we open, our father and daughter bookie operation is defunct.

∆

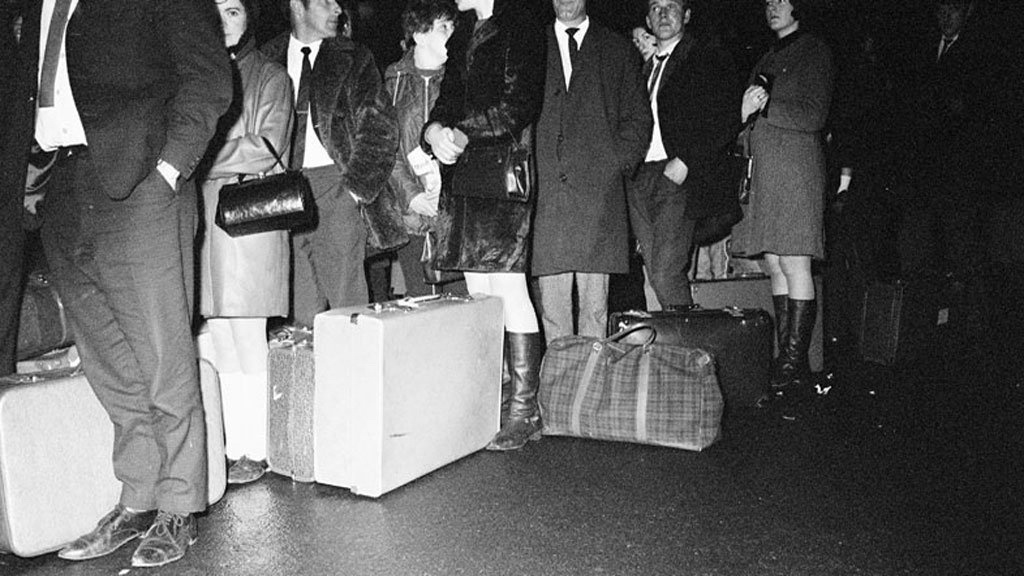

From the 1980s onwards recession had a serious grip on Dundalk. The town was wrecked by it, and if it was hard for my father to find a job in the late-1970s it was impossible in the 1980s. Once I completed school, I made my own way – my return – to London. I turned down a place at Trinity College to take a chance on my writing and my need to live in a freer environment than Catholic Ireland. I took the boat to Holyhead and the train to London. (A woman stopped me in Dun Laoghaire and gave me a holy medal and literature about help in the UK for the Irish; I threw them away.) I was not at all sad to leave; I was excited. Later, years later, I would be very sad indeed. But at this time I had no thought for my parents and realise now how distraught they must have been to have lost me, and not in the way they might have hoped. But I was hopeful, smart enough, and not pregnant (which would have been their worst nightmare).

After a few months, I got a job writing for a music magazine. When the magazine folded I remained in publishing and began to study drama and contemporary dance in the evenings. I followed this with a degree in Dance and English at Middlesex University, while simultaneously studying drama at the Lee Strasberg Institute. Soon, my sisters followed me to London, and after his studies in Galway, my brother emigrated to the US. My father also left Ireland and came to live with me in Kilburn: that is a whole other story.

As a regular theatre-goer at this time, I went to a lot of plays in London by Irish writers: Conor McPherson, Frank McGuinness, Marina Carr, Tom Murphy, at theatres such as The Tricycle and the Royal Court. I began to think that maybe plays were a way for me to tell my stories, my second-generation Irish stories, my Dundalk stories, even my father’s Irish stories, and after studying on the Director’s Course at The National Theatre, I began to write plays and fiction. I got a literary agent and was later accepted for my Master’s at Trinity College in Dublin to study Creative Writing and Anglo-Irish Literature.

Despite an explosion of Irish plays on UK stages in the 1990s, in terms of second-generation Irish playwrights there really was only Martin McDonagh. In terms of fiction, I wondered where were the second-generation Irish equivalents of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Hanif Kureshi’s Buddha of Suburbia? There was the brilliant The Grass Arena by John Healy, but this is more memoir than novel – searing and beautifully written as it is (reprinted in 2008 as a Penguin Modern Classic). Why such reticence from one of the largest – if not the largest – ethnic minorities in the UK? A possible reason for this could be that between the 1970s and the mid-90s, the IRA bombing campaign in the UK meant that the Irish and second-generation Irish, especially in London, did not stick their heads above the proverbial parapet. Also, historically, the Irish did not organise in the UK – unless it was for the Church. And besides, if you are ‘keeping your head down’, or plan on ‘returning to Ireland’ (which my parents had said they wanted to do for fifteen years), imminently or otherwise, you are probably not going to form a group for your interests.

Get the best of Moxy directly in your inbox.

The Irish-born experience and second-generation experience in the UK are inseparable, but they are not the same. For the second-generation Irish, it is easy to assimilate, and, you know, why not? In this global and digital age, ‘cultural identity’ does seem rather an odd term. Nonetheless, an increasingly plural Irish Diaspora is going to have stories and experiences to relay, and without resorting to any kind of taxonomy of Irishness, these stories and experiences need to be told and shared and read and staged.

While at Trinity (in Dublin), I felt the pull to return full-time to Ireland. My father, who had returned again, was ill, and my writing seemed to pour forth in this more confident, more modern ‘Celtic Tiger’ Ireland. It took a while to make the move, but in 2007 I left London once again.

MANY FRACTURES MAKE A MOSAIC

As Ursula Le Guin states, ‘true Journey is return’. I now live in Ireland, in Dundalk, and have done (this time round) for thirteen years. I survived the 2008 recession (just about) and wrote my plays Leopoldville, Belfast Girls, The Naturalists and my story collection The Scattering under its often malign influence. I also got to spend time with my much-adored (however flawed) father in his final years.

There are things I love about living here: the pace, the land. I’ve more living space than I had in London. I grow vegetables, have cats, I got married. At one point I even reformed the electronic band I’d been in as a teenager. Ireland is a much more multicultural society than it was. After a long hard fight, there is gay marriage and abortion rights. The Church has lost much of its influence. But as the years passed, I began to be reminded of some of the more subtle reasons why I left in the first place: the bureaucracy of institutions, the deference to authority, still that peculiar, irrepressible conservatism. These things take a while to detect. I also miss London a lot: the vast amount of galleries, the anonymity, my friends and family who are still there, the streets of Notting Hill, Kilburn and Willesden – places I once lived in. I find I follow British politics as much as Irish politics (especially since the Brexit Referendum). I listen to Radio 4. I miss the ‘state’ of being second-generation Irish in London; this amorphous group feels a little like ‘my tribe’ – people for whom Ireland is their country but London is their city, and no doubt some small town in Ireland is their town. In Ireland, bizarrely, I sometimes feel like a guest; my accent is often commented on, funnily enough mostly outside Dundalk. It’s also been commented on in the UK, where people often think I’m Australian. But if, as Naguib Mahfouz states, ‘home is where all your attempts to escape cease’, it would appear that after thirteen years I am probably home.

A note about emigration: what does emigration do to the people left behind? I spoke to someone recently who didn’t emigrate from Ireland in the 1980s, though many of his friends and family members did. He said something fascinating: as Irish people tend to focus a lot on family and community – when this is disrupted by a wave of emigration, the group at home goes through a kind of grief for those who’ve left: the group is also fractured by emigration. We emigrants and children of emigrants tend to forget how much we are missed; we fail to realise that friendships, which in another time or country might have been life-long, are strained and broken by leaving; that business ventures, bands, organisations that had bonded people together at home often break down after people leave. Such cracked connections and relationships can be difficult to repair. My father often said that his best friends in Ireland were not the people he’d known before he’d left but those who, like him, had also lived in the UK and had come home.

When my family first moved from London to Dundalk it was a complete culture shock. My siblings and I were kids from London. We had the freedom of London’s streets and often got on buses into central London by ourselves. Yet the Dundalk kids we played with seemed a lot tougher; you would think we were the sheltered ones. They swore, and said strange things about our and other people’s mothers. But, overall, they accepted us, and eventually, we settled in well. I’ve thought about why this was; Dundalk was a dour, rough town after all. But actually it makes sense. We were second-generation Irish children coming to a border town that was itself fractured, army on one side, British helicopters regularly in the skies above; a town often disparagingly referred to as El Paso or Bandit Country, despised by the Dublin Government. Dundalk was also chock-full with families escaping the 1970s pogroms in the North, as well as other returning emigrants. This border town was probably the perfect place for us. And it is no wonder then that when I began to write my stories and plays, I wrote especially about borders and was (and continue to be) so fascinated by them. I am, after all, something of a fractured borderland myself.

Jaki McCarrick is an award-winning writer of plays, poetry and fiction. Following her debut short story collection The Scattering, she was longlisted for the inaugural Irish Fiction Laureate in 2014. Her plays, which include Leopoldville, The Naturalists and Belfast Girls, have won numerous awards and been well-reviewed in The New Yorker and The New York Times. Jaki’s criticism has been published by the Times Literary Supplement, Irish Examiner, and Poetry Ireland Review. She is currently working on her second collection of short fiction and her first novel. @jakimccarrick