I was at the final winery I’d be visiting in the Chianti region, seated at a long farm table with others I’d met only an hour earlier, enjoying wine pairings with a seven-course meal. The next day I’d board a train south to Chiusi, near the Tuscan-Umbrian border. I’d been accepted into an artists’ colony and would be sharing a villa with five housemates for two weeks, one of several on an estate nestled in a tranquil hamlet in the Cetona foothills. Thirty of us from across the United States, Canada, Europe, and as far away as Australia were coming together to write, paint, sculpt, photograph.

What struck me about my acceptance email, which had come on a clear, cold January morning in New England – beyond the thrill of being accepted – was the residency’s start date: October 6, 2018.

On October 6, 2009, I’d spent nearly twelve hours face down on an OR table, locked in a head vice while my skull was sliced open. I’d been diagnosed with a bleeding brain tumour. I spent a week in ICU, several more days on the hospital’s neuro-recovery wing, and close to a month at a brain injury rehabilitation centre. I learned to walk, swallow, and grasp objects again –relearning all the while that trying to rush my return to health wouldn’t serve me or bring optimal results. Patience was foundational, shaping my days and challenging my mind to let the required time pass as part of my healing. One way that helped was to plan trips in my head, ways I’d mark my surgery date each year thereafter to celebrate my second chance.

Back at the winery, we were into our third bottle between six of us. An Englishman beside me reached for a waiter’s sleeve as he rounded our end of the table, arm outstretched to offer fresh pours of a medium-bodied Chianti. Could he sample plain, local grape juice, the English gent asked, while we waited for the next course?

The waiter’s eyebrows lifted. ‘Moscato Bianco?’

‘No, not white wine. Grape juice. If you have it? I’m curious what your local grapes taste like before they’re barrelled.’

‘Moscato Bianco, yes?’ The waiter cocked his head.

‘No. Grape juice,’ my neighbour repeated. ‘Plain?’

The waiter left and soon returned with another bottle, smaller, skinnier than the bottles of red we’d been sampling. He showed the label to the Englishman.

‘Grappa,’ he explained. He wagged a finger. ‘Better at the end, for digestion.’

We still had a second meat course, a cheese and fruit plate, and dessert coming.

He poured a measure. Our small group watched the Englishman bring it to his lips.

The waiter chuckled. ‘Strong, but you try.’

The Englishman shrugged and tipped the glass of grappa, which at 80 proof was more than he’d bargained for.

The next day I arrived at the colony, stepping onto its grounds in late afternoon, mist settling over hills. Windows from surrounding villas glowed amber with the approaching evening. Over the two weeks that followed, I’d wake each morning at six-thirty to write at a picnic table on a stone patio. I’d reward myself after two hours with a cup of coffee, sitting under a cypress tree on a slatted lawn chair overlooking boxwood hedges. I thought about my good fortune, the chance to stay in a cluster of medieval stone villas that cling to the hillside as grapes to vines. I worked to uncover what I went there to find, a way into my memoir. I thought, too, about the wineries I’d visited the week prior.

Wine production is a two-fold process: viticulture – the growing of grapes, and vinification – winemaking. Vinification has two phases: fermentation and finishing, or maturation. After fresh juice has fermented into wine, it needs to ‘settle down’ in order to lose its rough edges. To mature.

∆

Stage 1: Harvest

Weather plays an important role during growing season, but it’s the moment at which grapes are picked that determines a wine’s flavour and acidity. The timing of harvest is critical.

Harvesting, they told us, can be done by hand or machine. Machines can negatively affect grapes, sometimes breaking them, and it can be taxing to the land. This leads many vintners to choose the more laborious handpicking process. Once picked, grapes are taken back to a winery and sorted, where under-ripe and rotten ones are culled.

I take myself to task often, disappointed that I haven’t finished my memoir. It’s now ten years since my surgery, yet still I refine my story, reworking passages again and again with writing peers. My mind nags at me that I should have completed it long ago.

The seed of my story, the memoir I’m writing about my lifetime with a mysterious brain tumour, needs to be handled carefully. I need to balance timing and process to handpick the right pieces, the most compelling moments.

A harvest rushed, one vintner pointed out to us, can be a harvest wasted.

I’m reminded of my impatience with my recovery. I wanted faster results, whether it was strengthening my vocal cords to speak and my swallowing reflex to eat, or asking my physical therapist if I really needed to use that walker. Why couldn’t we skip that part, I asked, and go right into trying a cane? The walker made me look and feel old and feeble, the cane a little less so. We could jump to the cane, my therapist answered, so long as I didn’t mind landing on the floor. I’d get there, she reminded me, and eventually would walk again unassisted – but first I needed to put in the time.

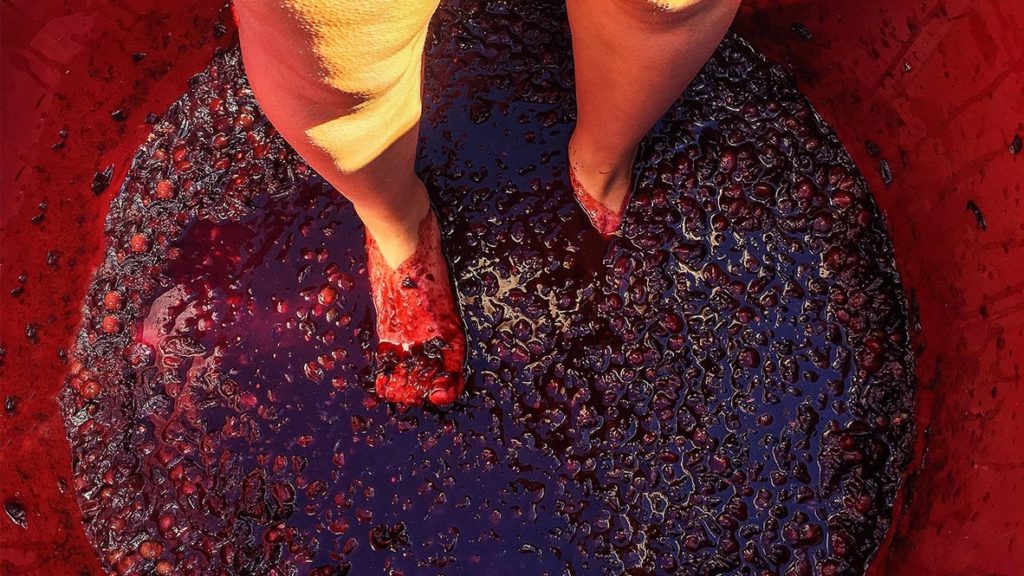

Stage 2: Crushing

After sorting grapes into bunches, they are de-stemmed and crushed. Many wineries offer visitors the opportunity to squash grapes underfoot as part of a tour package, the experience harkening to a romantic yesteryear when this was the primary crushing method. More often, wineries crush grapes mechanically to more quickly meet business demands. Needless to mention, it’s also more sanitary.

Crushed, fresh grape juice is called must–what my English tablemate apparently wanted, before he was upgraded to 80 proof liquor. Must contains grape seeds, skins, and sometimes small chunks of the fruit’s flesh. When making white wine, these remnants are skimmed while in holding tanks, to prevent tannins from leaching into the product. With red wine, it’s left to soak in, infusing additional flavour and colour.

I’d nicknamed my brain tumour Angie. I had a neurovascular disease, a cavernous angioma, a tumour that bled. As frightening as it was to finally receive a diagnosis at forty, after years of puzzling and worsening symptoms, what shocked my family and me even more was learning I’d had it my whole life.

I press and extract my memories. I skim seeds and skin from my drafts where I want my story crisp, like a white wine. Where my story is better served with more weight, I leave bits in to colour it.

Stage 3: Fermentation

Vintners add yeast to must during fermentation, which combines with sugars to start turning it into alcohol. Some winemakers prefer wild yeast, others, cultured yeast that can help with product consistency. Fermentation starts within six to twelve hours and can take weeks to a month to complete.

When all sugar converts to alcohol, the vintner will have produced a dry wine. For sweeter wine, they’ll stop the fermentation midway.

As my story evolves I add knowledge gained since my surgery, combining it with experiences I lived. I break down clues revealed to me across decades, turning it into insight. I give my story, as I needed to give my recovery a decade earlier, the time it needs to rest and emerge.

Stage 4: Clarification

Clarification is the first step in maturation. Tannins, proteins, and dead yeast are removed through filtering. Some winemakers filter by adding clay to their holding tanks. Unwanted particles are drawn to the clay that eventually sinks to the bottom. After clarifying, the wine is transferred into another tank and prepared for aging or bottling.

I sift through memories, trying to explain – to understand – how I got to the age of forty without knowing that a brain tumour had shaped who I’d been all my life. How I’d experienced everything up to that point through a lens that included Angie.

Memories from toddlerhood escape me, yet from what I now know, Angie was there. The culprit behind my crossed eye at age four, the reason I limped from kindergarten into adulthood, the demon behind my thundering headaches, severe enough to make me vomit, dry heave, hiccough without pause. I woke with Angie every morning, fell asleep with her every night. Her presence constant. Her threats intensifying.

Ten years on, I’m still clarifying what it meant to live with Angie. I’m still filtering what it’s like to live without her, with time deepening my understanding and gratitude.

Stage 5: Aging and Bottling

If wine is to be sold immediately, it will be bottled. Otherwise, to age red wine, the product is transferred into oak barrels that can add a rounder, smoother, sometimes vanilla-like flavour. Barrelling introduces oxygen which mellows tannins. Steel tanks are preferred to age white wine.

After a pre-determined span of time, anywhere from one year to ten or more, the wine is bottled and corked, bringing a higher price and offering a more sophisticated taste. The consumer enjoys a better product because the wine has settled down and matured.

I talked with an acquaintance five, maybe six years ago, about the pressures writers put on themselves to churn out their stories. She’d survived breast cancer, self-published within thirteen months of her last treatment, and was disappointed in the final product and lacklustre response from the small readership she’d been able to reach. It was as if she’d pasted a shelf life sticker on a defining part of her life’s story. She’d rushed to get it on the page, get it out the door. She asked if I’d follow a similar route. I told her I worried about leaving my real story untold if I worked against a self-imposed clock. I wanted time to let my memories mature.

Stories are about timing, extraction, fermentation, clarification. Stories can be spicy or floral. Smoky or smooth. Rough or round. Heavy, light, tart, fruity – depending on what we invite into our recall. I allow my recollections to settle down in service to my story. As with winemaking, as with my recovery, the passage of time is needed to shape the result.

Ann Kathryn Kelly lives and writes in the United States, in New Hampshire’s Seacoast region. She’s a Contributing Editor with Barren Magazine, works in the technology sector, and leads writing workshops for a nonprofit that offers therapeutic arts programming to people living with brain injury. Her essays have appeared in X-R-A-Y Literary Magazine, Lunate, The Coachella Review, Under the Gum Tree, the tiny journal, and elsewhere. ![]() @annkkelly

@annkkelly