CREATIVE NONFICTION

BOOK REVIEWS

This page contains reading recommendations for creative nonfiction books, which we also share on our Instagram page.

If you choose to buy the books we recommend using the links provided, 10% of the cover price will go to Moxy, at no cost to yourself. Want to buy a different book but still support Moxy? You can do so by purchasing your choice through our page on Bookshop.org. Thank you in advance for your support!

Would you like to contribute a creative nonfiction review to this page?

submit a creative nonfiction review

22 february 2021

Catholic priests are not allowed to marry as a rule, but there is one loophole: marry as a Protestant minister and convert to Catholicism. This is how Patricia Lockwood’s father became one of the few Catholic priests in America permitted to have a wife and children.

But Greg Lockwood’s unconventionality doesn’t end there. An ardent Republican, he has an enduring dislike of cats whom he fiercely believes to be Democrats. His unpriestly habits include wielding guns, swearing, and sitting in bed shouting at the TV with no regard to his family wincing in the living room below. He’ll likely be watching a trilogy. Why? Because trilogies are sacred, reminding him of the Holy Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Famous trilogies are wildly reinterpreted in the light of Catholicism: Star Wars is ‘about priests in space’; the first three Alien films are ‘about how all women are destined to be mothers’, and the Transformers movies are a particular favourite ‘because the greatest Transformer of all . . . is Jesus Christ.’

But Patricia doesn’t share her father’s beliefs. Brought up religious, she has now lapsed. This means she is an astute observer of her father’s eccentricities, positioned as she is outside his religion but inside the family. This comes to a head when Patricia and her husband are forced to move back home because money is short, resulting in the hilarious memoir about her time there, ‘Priestdaddy’, which is our creative nonfiction recommendation this week.

4 february 2021

God may be dead but when did he ever let that stop him?

Emmanuel Carrère is a successful writer and reflexive secularist, who has never felt any compulsion to religious belief. In this he is typical of a majority of French citizens. But despite its enshrining of laïcité, France remains the home of Mont St Michel, of Notre-Dame and Rheims cathedrals, a nation with deep Catholic roots. Its religious ghost is always liable to rear from the tomb and bite back.

This is what happens to Emmanuel at a moment of crisis, depressed and paralysed, his work at an impasse: to the shock of his friends he converts to Christianity, attending Mass every evening and spending each morning writing a commentary on the Gospel of John.

The Kingdom traces this conversion, from fervent beginnings to its petering out two years later. But what makes it a far richer, far more provocative book is its second half, a novelistic retelling of the spread of Christianity through the Roman Empire after Jesus’s death. The historical sources leave multiple gaps, which Carrère fills with aplomb. For him, Luke is the central author of what we now know as Christianity. He is painted as a peripheral figure in his lifetime, one among many followers of the far more charismatic Paul. But his writing, with its own portrayal of Jesus and Paul, wins the battle for posterity.

Carrère’s ideas are unsettling and his insertion of himself into the story of the early church monstrously egotistical. But it is a knowing egotism, replete with sly humour, which takes place in a book that could only have been written today. The Kingdom is very much a twenty-first century Resurrection, and is our creative nonfiction pick this week.

27 december 2020

Perhaps the last thing you want to read right now is a book of essays about the coronavirus. But if you are going to choose any writer to read about the pandemic, that writer should be the inimitable Zadie Smith.

Smith’s latest collection of essays is Intimations, written during the spring lockdown and published over the summer. It’s a slim, stylish volume–the perfect read for a cold winter’s day when there’s little to do. The fine-grained sense of detail and sharp wit Smith displays in her fiction are equally present in these essays. Like the sprawling White Teeth, which explores family history, inheritance, and the tense politics of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Intimations takes on a wide variety of subjects.

Smith’s essays zip easily between the past and the present, as well as personal reflection and broader political discussion. And each piece offers a novel, bracing critique: of Trump’s America, of cultural assumptions surrounding pain and suffering, of the value of art in an era of turmoil. It’s a testament to Smith’s masterful command of the genre that these varied essays rarely become cluttered or confused.

In Intimations, Smith casts a dark but judicious eye over a strange, shifting world. Yet she never falls into paroxysms of self-absorption, as some writers have in their own pandemic essays. This book is considered, thorough, and deeply felt: stimulating, but tender, too. Oddly enough, these might be some of the most comforting essays you’ll read this year. A must-read from one of the most clear-eyed, original thinkers of our age.

7 november 2020

‘The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.’

With these words, Vladimir Nabokov begins his bid, armed only with his wit and the sharpened point of his pencil, to pry open that crack of light and bathe us in the splendour of his reminiscences.

Speak, Memory is one of the greatest memoirs ever written, by perhaps the finest stylist of modern English prose. Nabokov possesses not just tremendous literary skill, but also a life that, in its dislocations at the tender mercies of history – born into the Tsarist aristocracy; beneficiary of a vast fortune at the age of seventeen, which he lost a year later in the October Revolution; safety at first in Berlin, then his father’s assassination; flight to Paris after Hitler’s rise to power; flight to America after his invasion – makes for a captivating story.

The book is possessed by the problem of time – how it is lost, and how to recapture and preserve it. It is patterned like the marbled wings of a butterfly; small images stand for later incidents, as the hind wings of the adult Parrhasius m-album mimic its forward-facing eyes and antennae. An especially vivid moment describes the prize results of Nabokov’s mother’s mushroom hunt:

‘…there, on the damp round table, her mushrooms would lie, very colourful, some bearing traces of extraneous vegetation – a grass blade sticking to a viscid fawn cap, or moss still clothing the bulbous base of a dark-stippled stem. And a tiny looper caterpillar would be there, too, measuring, like a child’s finger and thumb, the rim of the table, and every now and then stretching upward to grope, in vain, for the shrub from which it had been dislodged.’

Like the blade of grass, the clinging moss, the clambering caterpillar, our narrator too has been dislodged – deprived of his inheritance and exiled from his homeland.

Speak, Memory is Nabokov’s way of reviving this lost world. With its captivating sentences, visionary attentiveness, and ingenious structure, it is our book of the week.

21 october 2020

‘Suppose I were to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a colour…’

Maggie Nelson’s Bluets is a difficult book to categorise or even describe. Superficially, it is about the author’s infatuation with colour blue. Consisting of 240 discrete sections ranging from a single sentence to a page in length, Bluets delves into subjects as diverse as pornography (blue movies), Goethe’s Theory of Colours, melancholy (the blues), and Joni Mitchell. Its lightly sketched narrative tells of Nelson’s breakup with the mysterious ‘prince of blue’ and her subsequent obsession.

She collects blue objects, begins a correspondence with ‘a man who is the primary grower of organic indigo in the world’ and meditates on desire, loneliness, love, friendship and sadness. A typical observation is the idea that our perception of colour, which begins fifteen days after birth, in creating ‘forms out of what is essentially shimmering’, might in fact be ‘the source of our suffering.’

Bluets is prose, poetry, philosophy, criticism and memoir all at once. Strikingly written, at times opaque, it is always interesting and shows how much can be accommodated within the (ever-expanding) boundaries of nonfiction.

19 september 2020

This electrifying book was first published in 2018 but has gained new prominence since the recent Black Lives Matter protests.

It tells two stories: that of Akala’s own childhood growing up poor and black in London, as well as the wider story of insidious injustices built into UK institutions.

Akala moves from detailing some of the horrific racism he has experienced in his own life, including a teacher who told him that ‘The Ku Klux Klan stopped crime by killing black people’, to zooming out to the wider problem, such as the fact that black students are consistently marked down by teachers as compared with the anonymous grades they receive from SATs.

He scrutinises why the idea of ‘black-on-black violence’ has gained such currency, when violence between whites is never classed as ‘white-on-white’. He argues that black people are deemed to be implicated in other black people’s failings in a way that white people are not: some of the most horrific crimes of recent years, including the murder of James Bulger, were committed by white people but did not spark national conversations about a ‘white problem’.

If your eyes have already been opened by the events since the death of George Floyd, Natives will open them wider. Akala calmly and rationally dismantles the idea of racial impartiality in British institutions including the police, schools and the media. A powerful blend of history, polemic and memoir, Natives is our creative nonfiction pick this week.

13 september 2020

‘It’s the nuances of desire that hold the truth of who we are at our rawest moments. I set out to register the heat and sting of female want so that men and other women might more easily comprehend before they condemn. Because it’s the quotidian moments of our lives that will go on forever, that will tell us who we were, who our neighbors and our mothers were, when we were too diligent in thinking they were nothing like us. This is the story of three women.’

Lisa Taddeo spent 8 years living alongside Lina, Maggie and Sloane, the three women whose lives form the narrative of this book.

Seventeen-year-old Maggie is reeling from a relationship with her teacher; Lina is turning away from a loveless marriage towards a high-school sweetheart; Sloane is a happily married restaurant owner whose husband likes to watch her have sex with other people.

The book sets out to explore women and desire, but has been criticised for focussing on too narrow a class of women: Maggie, Lina and Sloane are all white, American and from Christian backgrounds.

But whether you read the book as a study of female desire in general or simply of Maggie, Lina and Sloane’s desires, Three Women is a paragon of creative nonfiction writing: scrupulously researched and factually accurate, but written with the psychological detail of a novel.

29 august 2020

Ryszard Kapuściński’s Shah of Shahs is a pioneering work of creative nonfiction, yet it remains underappreciated in the Anglosphere. Kapuściński is a unique figure among foreign affairs journalists: he sought out the chaos of war and revolution, fascinated by humanity’s behaviour at the extremes of experience, which he went on to detail in highly allusive, poetic, and subjective accounts of history. For this reason academic historians have accused him of manipulating the truth and of claiming he was present at events that he did not witness. In his defence, the reader knows within a few pages that this is not ordinary history but something closer to a fever dream or myth.

Shah of Shahs recounts the Iranian revolution of 1979 in which the last Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, was overthrown. Kapuściński is seemingly the last foreign journalist left in the country, having idly missed the opportunity to flee. Stranded in his hotel room with ‘heaps of index cards, scraps of paper, notes so hastily scrawled and chaotic’ left all over the furniture, he spends his days wandering through the uncertainly free city of Tehran in the immediate aftermath of revolution, when no organised force has yet seized control.

The story of the revolution and the dictatorship preceding it is told mainly through photographs. A picture of the Shah’s father Reza Pahlavi, prompts an account of the dynasty’s ascent from peasantry to absolute power and then to exile in two generations. A picture of people at a bus stop, with one man ‘inclining his ear towards three other men talking’ reveals the omnipresence of Savak, the secret police, who ‘had a good ear for all allusions’; words like ‘darkness, burden, abyss, collapse, quagmire, putrefaction, cage, bars’ cannot be spoken.

Kapuściński uses his limited perspective to give an impressionistic account of being caught up in history as it happens, with no one knowing what will come next.

8 august 2020

You might have seen this book before: on the bookshelf of a trendy influencer, clutched by a model in an Instagram post, held up by a fashionable reader on a train. Of essay collections published in the last year, none has been as well-received as Trick Mirror, by New Yorker staff writer Jia Tolentino. Like a viral meme, the book — a collection of essays on the Internet, contemporary feminism, morality, and life under capitalism — secured a spot in our cultural zeitgeist, becoming a trend in and of itself. Having Trick Mirror on your bookshelf is a surefire way to signal cultural awareness, and to perform yourself as an in-the-know media consumer.

Ironically, much of Trick Mirror inveighs against performativity, and as a work of nonfiction, it’s far more complicated and rich than its mainstream reception — as a covetable literary accessory — would suggest. Tolentino is best known for her precise, and eminently readable, cultural round-ups in the New Yorker, and many of the book’s essays qualify as cultural criticism in this vein. Others, though, are more personal — about Tolentino’s stint on a reality TV show as a high schooler, or her childhood in Texas, where she attended a megachurch but became an avid hip hop fan. Tolentino is most interested in contradictions such as these, both in her own life and in American culture writ large, and reaches no easy conclusions about what it means to be a millennial, a consumer, or a feminist today.

Does Trick Mirror still live up to the hype? Though much has changed in the year since the book was published, Tolentino’s essays are still essential guides to the systems and structures that organize our lives. Tolentino frets about our mediatized, manipulative world, and the way in which we’re often asked to perform or market ourselves to a watchful audience.

Yet Trick Mirror is also a testament to the authentic joy and respite to be found in certain universal experiences: reading, writing, partying, friendships. Tolentino’s style of criticism is neither rigid nor relentlessly negative; rather, it’s capricious and witty. It’s also far more optimistic than it might seem — not unlike the deceptive image produced by a ‘trick mirror.’

2 august 2020

Pablo Picasso lusted after her. Jack Nicholson offered her cocaine. Peter Sellers was in love with her.

Princess Margaret, the Queen’s only sister, was the diva of the British royal family. She loved to keep dinner guests waiting for hours (no-one could eat before she arrived), or to sweep into a casual lunch inappropriately overdressed. She lorded her status over everyone; yet she was the first major royal to marry a commoner.

Craig Brown attacks Princess Margaret’s life from many angles. Rather than plodding along dutifully from birth to death, each chapter of Ma’am Darling presents a scene, a parody, or an alternative history: how would Princess Margaret’s marriage with Picasso gone if he had succeeded in wooing her? How would Elizabeth have behaved had she been second in line to the throne? What would a Christmas speech by Queen Margaret look like? (Salty as hell)

Irreverent and very funny, Craig Brown presents Princess Margaret as a rude, status-obsessed, totally out-of-touch royal whose antics question the place of that elite institution today. Ma’am Darling is a wickedly playful, formally inventive biography, and our creative nonfiction pick of the week.

23 July 2020

VS Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival is subtitled A Novel in Five Sections, but knowledge of his biography — of a clever boy from Trinidad who won a scholarship to Oxford; a young man who then established himself in London as a writer, who, with difficulty, succeeded and found success difficult; a middle-aged man who moved away from the metropolis to a cottage in the grounds of a crumbling Wiltshire estate — this biography seems entirely inseparable from the narrative of the ‘novel’ we are reading.

But that does not make it an autobiography in any usual sense. The book is a microcosm, focused entirely on a few years in Wiltshire, with one section about Naipaul’s first journey from Trinidad to England. To confuse things further, Naipaul confirmed that some of the events recounted did not take place: the story of a neighbour who murders his wife, for instance. But these events are all peripheral and the way he writes about them is not all novelistic.

The real subject of the book is the growth of the writer’s consciousness and his acclimatization to an alien environment. Slowly, he learns to see the Wiltshire landscape — so different from that of Trinidad — for what it is, to separate it from the image of England he has gleaned from books. He learns the names of trees, and he connects the history of Trinidad to the history of the manor, distant though they be.

Naipaul said of the English landscape: ‘So much of this I saw with the literary eye, or with the aid of literature. A stranger here, with the nerves of the stranger, and yet with a knowledge of the language and the history of the language and the writing, I could find a special kind of past in what I saw; with a part of my mind I could admit fantasy.’

The Enigma of Arrival is one of the strangest works of postcolonial literature, a genre-blurring masterpiece and an overlooked precursor to the meditative narratives of WG Sebald and Teju Cole. It is our creative nonfiction pick of the week.

3 July 2020

What could be more timely than a book about the apocalypse?

Mark O’Connell is no armchair philosopher. In Notes from an Apocalypse he does the legwork, visiting the almost exclusively male ‘preppers’ who look forward to the end of civilisation as a time when patriarchy can be reinstated, and meeting disciples of Elon Musk’s project to ‘colonise’ Mars in preparation for Earth becoming uninhabitable (as if Mars isn’t). He ventures to the radioactive zone around Chernobyl, goes hiking with climate catastrophists, and tours commercial bunkers offering protection from the apocalypse, all with a healthy sense of irony about his inevitable carbon footprint.

Like a more sarcastic Louis Theroux, or a less self-indulgent Jia Tolentino, Mark O’Connell is a probing, funny and cynical cultural critic. A seamless blend of memoir, travel and criticism, Notes from an Apocalypse is creative nonfiction at its very best.

20 june 2020

‘What do you do when you cannot leave and cannot return?’

Our creative nonfiction book of the week is Hisham Matar’s poignant memoir The Return. After a lifetime exiled from his homeland of Libya as a result of his father’s activism against the Gaddafi dictatorship, the 2011 revolution finally allows Matar the opportunity to return to a land that, until that point, existed for him mainly in memories, in writing, and through the static of phone lines.

But it is not only to see the land itself — ‘rust and yellow. The colour of newly healed skin’ — that he returns. When Matar was nine years old, his father Jaballa was abducted from their home in Cairo and imprisoned in one of Libya’s most notorious dungeons. The family’s agony has been not to know whether he is alive or dead. Matar has lived for decades unable to mourn or hope, yet half-mourning and half-hoping all the same. To set foot in Libya again is the opportunity to dispel his doubt. But with opportunity, there is fear: what if the return does not dispel doubt, but confirms it? What if Jaballa, like so many others, has disappeared, without a record?

The Return is a beautifully written account of exile, family, and homeland, as well as an interrogation of the role of art and the artist in relation to a political system that denies art’s values: ambiguity, uncertainty, tenderness.

3 june 2020

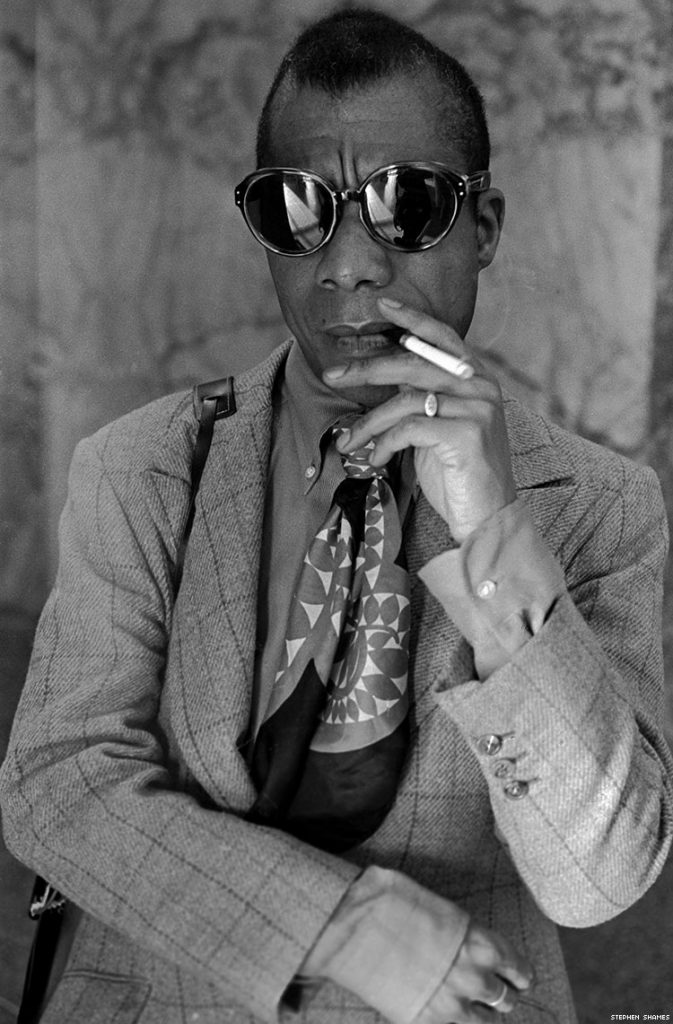

Recommended reading: ‘Notes of a Native Son’, by James Baldwin, one of the most important personal essays to come out of the twentieth century, and one of the most compelling, necessary works of nonfiction of all time.

Tracing his own upbringing, his relationship with his preacher stepfather, and his experiences with acts of racist aggression perpetrated by white Americans, Baldwin’s essay is an indispensable perspective on deep-seated injustice. The Harlem riot of 1943 forms a backdrop to Baldwin’s examination of his stepfather’s inner turmoil, a result of the vast disparities that characterized mid-century black life in the United States – where oppressive policies created untenable hardship.

Baldwin, too, discovers that he suffers from a ‘dread, chronic disease’, the devastating effects of racist treatment on his psyche and well-being: ‘once this disease is contracted, one can never be really carefree again.’ He ends the essay by arguing one cannot be complacent in the face of entrenched brutality and white supremacy. ‘One must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength.’

‘Notes of a Native Son’ is essential reading for our current climate, with particular historical import: in response to the George Floyd protests, New York City’s mayor recently imposed a curfew, the first to be mandated since the Harlem riot in 1943. Readers will be reminded that not enough progress has been made since Baldwin wrote powerfully of his experiences over fifty years ago.

25 may 2020

Anna Wiener’s dazzling memoir, Uncanny Valley, offers an insider’s view of Silicon Valley at the height of the start-up industry.

Lured by promises of affluence, new kinds of fast-paced jobs, and abundant workplace perks, would-be tech superstars flocked to California, a Gold Rush for the twenty-first century. Wiener expertly chronicles the darker aspects of life in this new technocracy: greed, corruption, sexism, and cultural homogeneity, all under the guise of meritocracy and ‘innovation.’ Wiener’s portrait of start-up culture is our creative nonfiction pick of the week. Acerbic, detailed, and intensively self-reflective, Uncanny Valley chronicles Weiner’s experience as an ex-publishing assistant turned tech worker seeking purpose and opportunity out west.

As Big Tech continues to exercise control over nearly every aspect of our civic lives, Wiener’s arresting narrative — compiled from years of careful observation, and rendered in pitch-perfect prose — asks us to reconsider our blind faith in Silicon Valley’s leaders, as well as its pervasive rhetoric and ubiquitous products.

18 may 2020

The German author WG Sebald would have been 86 today. He pioneered a unique style of writing, working somewhere in between a novelist, historian, and travel writer.

Our creative nonfiction book of the week is his masterpiece The Rings of Saturn, in which the mysterious narrator walks the Suffolk coast, taking in decrepit seaside towns such as Lowestoft and ruminating on how decay makes itself everywhere invisibly felt. The physical hike takes up few of the book’s pages; instead, Sebald’s focus is on his ranging mind, which brings in subjects as diverse as Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, the cultivation of silkworms, and the life of the dowager empress Tzu Hsi.

His melancholy peregrinations have influenced a huge number of authors writing today, including Teju Cole, Iain Sinclair, Jenny Erpenbeck, and Rachel Cusk. But none of them replicates the unique reading experience provided by Sebald. Happy birthday, WG Sebald!

6 may 2020

Craig Brown has been credited with re-inventing the biography – and the creative patchwork of stories in One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time is enough to show why.

Published just last month, One Two Three Four is a fantastically funny cultural history of the Beatles. Each short chapter focusses on a different element of the ‘fab four’ – from their iconic hair, whose relaxed style heralded the laid-back rhythm of the ‘60s, to how politicians tried to use the band to increase their social currency, to stories of wild parties brought vividly to life with characters including Judy Garland, Bob Dylan, and the Rolling Stones.

If you’re struggling to concentrate and in need of immersive distraction, the short, witty, and masterfully conjured chapters of this book could help. Biography isn’t usually classed as creative nonfiction, but Craig Brown’s unique storytelling method and the way he weaves his own personality into the retelling persuaded us to make this book our creative nonfiction pick of the week.

26 april 2020

‘People ask me: “Why don’t you take photos in colour?” In colour! But Chernobyl: literally it means black event. There are no other colours there.’

Today is the 34th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Some of you will have seen HBO’s dramatisation of the event, but the source of many stories in that show was Svetlana Alexievich’s intensely moving polyphonic history, Chernobyl Prayer, which is our creative nonfiction pick of the week.

Alexievich’s approach consists not of a single centralised narrative, but a combination of hundreds of discrete accounts by participants and witnesses including the wife of a first responder, a Belarusian scientist, and a nurse treating children suffering from cancer in the aftermath.

These oral accounts are arranged without any questions or interruptions by Alexievich, as if she were overhearing a hidden record. They combine symphonically, to paint an intimate picture of the ordinary human being caught up in this historic tragedy. As seen refracted through so many different accounts, history is transformed from something static and explainable to a chaos, whose impacts are wider-ranging and stranger than could ever be guessed.

15 april 2020

When Hisham Matar was 19, his father was kidnapped and imprisoned in Libya, where ‘gradually, like salt dissolving in water, he was made to vanish.’ Matar took to standing for long hours in front of paintings in London’s National Gallery, and developed an interest in the school of Siena. Twenty-five years later, he finally got the chance to visit the city whose art helped him survive his father’s death.

A Month in Siena is the result of this visit, and is our creative nonfiction pick of the week. A mix of memoir and art criticism, it is an absorbing read which invites us to keep pace with the author’s thoughts as he explores the city’s people and art galleries. The writer dips into the history of Siena, the habits of its museum guards, and the daily lives of its residents, between his detailed explorations of various pieces of Sienese art. If you’re missing the languid sense of exploration that comes with a visit to an Italian city, you’ll enjoy escaping into Matar’s wonderful prose.

21 march 2020

One upside of self-isolation is that it gives you a lot of time to get on with that novel you’ve been telling everyone for years that you’re working on. One downside of self-isolation is that you’ve got no excuse as to why that novel you’ve been telling everyone for years that you’re working on hasn’t actually been started. We can only imagine what coronavirus would have done to Geoff Dyer, as he found every reason under the sun not to begin his ‘sober academic study of DH Lawrence’ until conditions were perfect, which they usually were, at which point he’d discover a reason why they weren’t.

Out of Sheer Rage is a genuinely hilarious account of writer’s block (it turns out it really ought to be called writer’s sloth) at the same time (and in spite of itself) as being a brilliant study of D H Lawrence’s life and work. Dyer is a master at digression: we learn at length why all seafood is ‘vile filth’, why seatbelt warning lights are actually ‘a stupid and dangerous idea’, and why Italy ‘should not be allowed to show films.’ Dyer has perfected a uniquely English style of whining, yet uses his universal infuriation to breathe life into that most stale of genres: literary criticism. Out of Sheer Rage remains one of the finest examples of creative nonfiction and is a perfect read during this dark time for would-be-writers and the rest of us alike.

10 march 2020

You are wandering in a desert in what used to be, 10,000 years ago, the state of New Mexico. On the horizon, dark against the clear blue sky and the flat red earth, a black mass vibrates. As you approach, the heat haze clarifies and the mass resolves itself into a field of fifty-foot tall concrete spines – a gigantic field of thorns. Is this a warning – go no further for here be dragons – or an inducement to riches – pass if you can, for here be treasure? How to convey the former without implying the latter remains the question faced by the Human Interference Task Force, a group convened by the US Environmental Protection Agency to construct a system of signs to deter future beings from disturbing deadly subterranean repositories of nuclear waste, which will endure far beyond human reckoning.

Human beings have always been drawn underground, no matter the known and unknown dangers, even as they fear what they might find. This is the subject of Robert Macfarlane’s Underland, our creative nonfiction pick of the week. In it, the nature writer explores our fear of, and fascination with, what lies beneath our feet. He ventures to the Paris Catacombs; the underground river Timavo, which flows through the karst of northern Italy and Slovenia; the Apusiajik glacier in south-east Greenland; and the fungal network beneath Epping Forest in Essex. Time works differently in these places: rock flows, air freezes, and one-hundred thousand years is compressed into a few metres.

The underland disdains human scales. It is where we come to read our prehistory. Yet it also offers clues as to our own future; clues as to the changes coming as a result of climate change, clues as to how we will be remembered by the planet we briefly occupied. Strangely, it is Macfarlane’s most human book, his most thorough investigation into our relationship with nature. And it asks a question we must all be mindful of: are we being good ancestors?

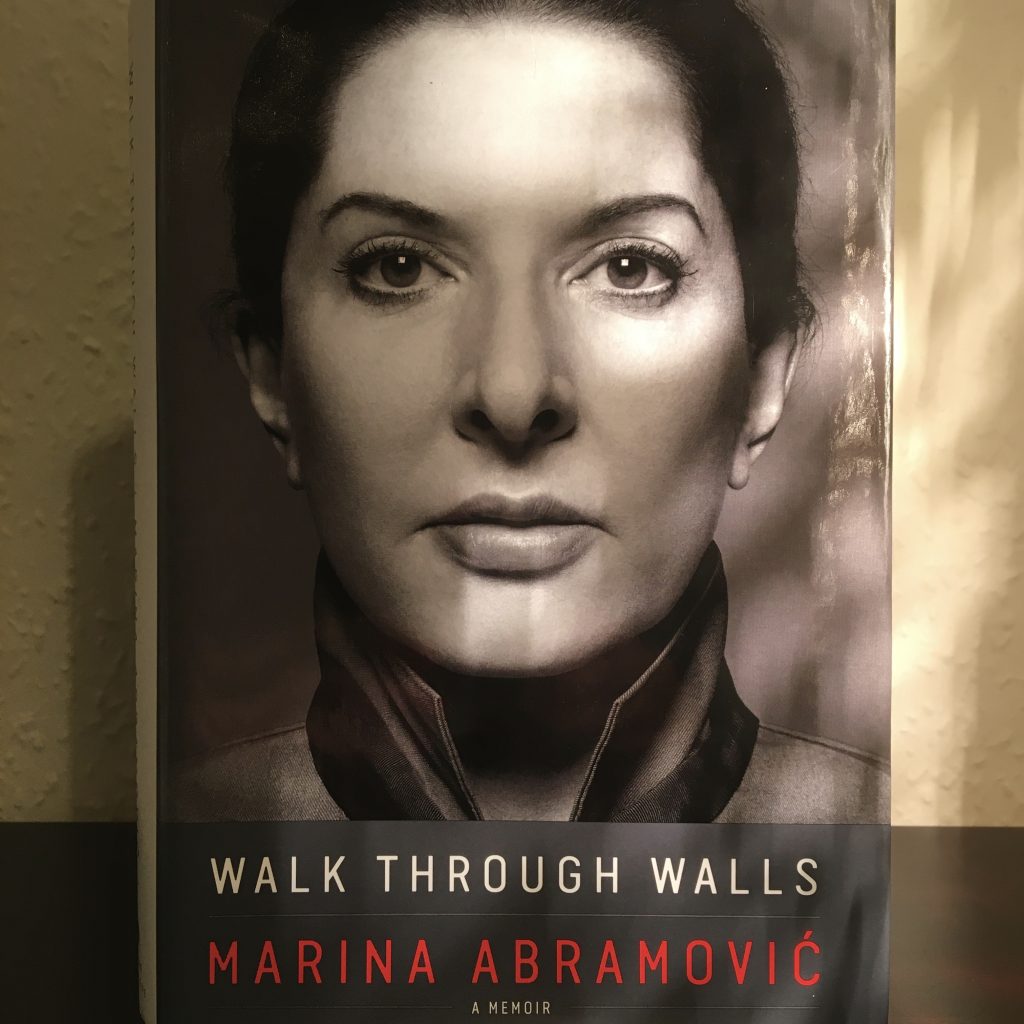

3 march 2020

You’ve sprained your ankle the day before you’re due to visit a Buddhist monk up a mountain. What do you do? Probably postpone or find some crutches. Not so Marina Abramović, the Serbian artist known as the ‘grandmother of performance art’. Instead, she made the unflinching decision to spend 5 hours crawling up hundreds of steps to see the monk at the arranged time.

This feat may seem extreme; but then so is her art. One of her most physically difficult pieces was The Artist Is Present in 2010. For 3 months, she sat in a chair across from members of the public for 8 hours a day. Those of us in office jobs think we can relate, until we realise that she didn’t eat, drink, urinate, or even shift in her seat. She broke her pose just once: when her former artistic and romantic partner, Ulay, sat before her. This moment of connection has become iconic, and the news of Ulay’s death yesterday has brought the image back to the public eye.

Marina’s memoir Walk Through Walls is our creative nonfiction pick of the week. In it, she tells the fascinating backstory to this image. This scene is not the first time Marina and Ulay sat across from each other in a performance piece: between 1981 and 1987, the pair performed Nightsea Crossing, in which they stared at one another for 8 hours a day, for 100 days. Ulay struggled physically with the challenge and would often walk away from the piece mid-way through. Marina sat through to the end, facing an empty chair. Cracks in their relationship began to appear; why hadn’t she walked away with him? Was finishing the piece more important than a show of solidarity with him? Their relationship fell apart shortly afterwards.

Decades later, this piece gave birth to The Artist Is Present. Whereas in Nightsea Crossing she had faced her lover, in The Artist Is Present she faced members of the public: her strongest relationship was now with the audience of her work. So when Ulay sat down in front of her, the pair mirrored their earlier piece: but while Marina had kept her pose decades earlier, in The Artist Is Present she breaks her stillness for the first time, reaching across to Ulay in a powerful moment of connection.