The Rodin Museum in Paris has a gallery dedicated to a single project by the sculptor: a statue commemorating Honoré de Balzac commissioned by the Société des Gens de Lettres, forty-two years after the author’s death. By all accounts, the commission dragged on, and the final plaster iteration of the monument was never cast in bronze during Rodin’s lifetime. Only in 1935, eighteen years after his death, was this more permanent vision enacted: the bronze is now situated in the museum grounds by the café. When I first saw the lurching, robed and moustached statue I couldn’t help but think of 1970s comedians, mainstays on prime-time TV when I was a child. Specifically, I thought of Bobby Ball, one half of the duo Cannon and Ball. All these men known by a single name.

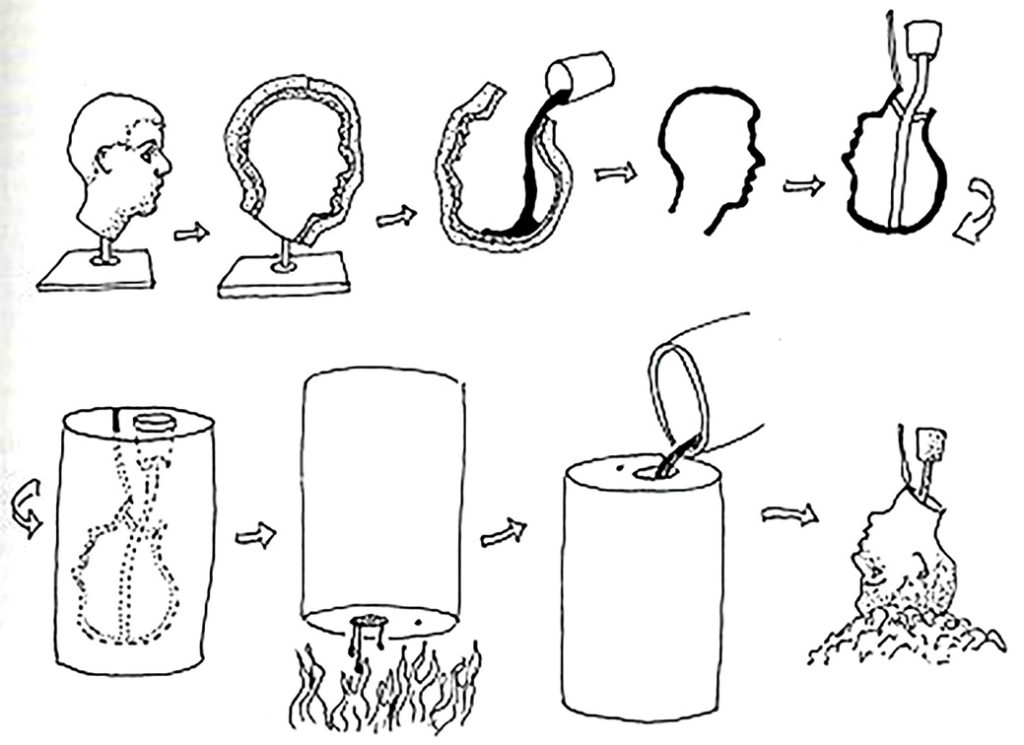

Inside the museum, at the centre of the Balzac gallery display, is a preparative work entitled Balzac, Étude de Robe de Chambre (Study for a dressing gown), made in 1897. The object is encased in a glass vitrine, into which it is a little hard to see, as reflections from the adjacent window obscure the view. A few accounts I read online suggest that to create the work, Rodin acquired a dressing gown directly from Balzac’s tailor, a replica of the one said to have been worn by Balzac when he was writing. The robe was soaked in plaster and then draped over the pot-bellied sculpture of the writer in Rodin’s studio – which, at the time of this experiment, he was struggling to finish. The version in the museum of the soaked and hardened robe has an aperture at the neck where you can see a wooden armature supporting the form. Unlike any other piece in the museum, this study had no figure – no actual body – only that which is described by the solidified fabric cover; the body’s absence is centre-stage. The idea of an absence describing an object in the mind of the viewer became a significant trope in visual art in the twentieth century – staging traces, memories, desires and oblique reflections on identity politics. Here, this vacancy stands in stark contrast to all the other sculpted figures – bodies that have been touched and tended to in their making, posed everywhere you look in the Rodin Museum and grounds.

This absent-body-man is a fantastical thing suggesting the writer shoulder-robing his way around his study. This plaster-robe-man; handless, headless – an exquisitely sculpted absence of the man.

∆

A year ago, my father and I met face-to-face, for the first time in ten years. We had exchanged several emails before the meeting. We had not spoken on the phone and had sent only text messages to confirm. I chose the place we would meet, a coffee shop in central London, just north of Oxford Street. I walked to the coffee shop from the bus stop at Oxford Circus. At the edge of the block, walking at a stuttering pace, I saw him ahead of me as he too paused before entering the cafe. He wore a light blue linen shirt. It was summer when we met.

I had worried immensely about the protocol of the meeting, the ‘who will be there first’ and what the appropriate greeting would be. I quickened my pace to catch my father as he entered the cafe. I remember thinking: don’t think, just do; go in; get on with it. I said his name, which sounded made-up, like a stereotypical name one might ascribe to an exaggerated character in a joke. As he headed to place an order, I touched his shoulder with my hand. He turned. He laughed nervously. He said something, I do not remember what. I looked at his face. I remember thinking ‘I need to do a quick survey, just to double-check it’s really him, to find out who he is now; his head, his face, his features, his eyes, his hands’. I remember the rushed look down. Does he still have all four limbs? Are his feet and hands intact? A paunch? This reaction felt akin to the first meeting with someone you’re attracted to, as you instinctively flash your eyes down their body, away from the face, towards their breasts, hips, thighs, crotch. I was reminded anew of male 1970s comedians. Only when you google them today, they have close-cropped hair and wear glasses. When they reappear on TV, on reality shows or as panel show guests, it’s only their mannerisms that suggest the person remembered from decades ago.

I had not rehearsed what I would do during the meeting, but I intuitively instigated a hug. The touching of my fathers back, as I entered the café, was the first point of contact, but the embrace was the most significant: this hold impeded by layers of cotton, no skin touching, just the brushing of surface area. From this, I could feel he was much smaller than I had remembered. I now think about the amount of knowledge I gained about him during that embrace, augmenting the facts and questions that preceded.

∆

I remember the first time my father hit me, which was also the first time I hit him. I don’t know who hit first. I suspect it was me; the only time I have to-date hit another person in the head with a closed fist. I don’t know if my father remembers this at all, and if he does, whether he would remember it as I do. The incident, arising out of a family argument, is a blur, sustained for what seems way too long. I remember thinking something like ‘if only he were not here, this would stop’. The quickest route? Knocking him unconscious. It was a lot harder than I had expected. Punching someone in the head is not like hitting a slab of meat; there’s no crisp thwack, but a slap against bone, the blunt strike of a fist against skull on top of a well-balanced body, with a well-constructed armature keeping the body upright.

I had always thought, when we met again, I would tenderly look into his eyes, then stand back and take a good look at the rest of him. I wouldn’t run away, and I wouldn’t push, barge or tussle. I would not spit or force or shout.

In the end, it was a meeting amongst strangers. These strangers were oblivious of the gaps in our meetings, the gaps in our knowledge of each other, the gap between our bodies, and the gaps between gaps.

Over coffee, we sat for an hour, undertaking something like catching up. I wish we had just sat in silence, attending to our discomfort. We were physically closer than we had been for years. We drank coffee. I had a green tea, which was only lukewarm; the glass pot was not well cleaned, tannins had stained the glass.

Why had I taken this journey back to this place, where our bodies could touch? Perhaps it would have been easier never to have seen my father again, to have sustained the image I had of him as the man who hit me, the hitting man, which had served me well in anger? Now, this image was ruined.

∆

My sister’s husband is dying. He has terminal cancer. I know this from a text message; I have not heard it spoken. My mother told me the tumour began somewhere in the region of the throat, or perhaps the oesophagus. I think of the years of liquids and food that have passed through that channel. I imagine the surgery: parts of the body ruined, parts of the body taken away.

My sister and I arrange to meet via text. I plan to travel to her, to meet for an hour. I can’t trust the writing in her message, clipped and far away. I want to be able to sit with her just for a while, maybe not even talk. I decided not to tell her that my partner and I have also been spending time in hospitals, undertaking fertility treatment. I decided I would not speak of the IVF and embryo transfers – attempts to make a new life. My sister cancels our meeting; she sends a photograph instead. In the recent image, she is running in a marathon. The picture of her body is cropped and incomplete. As she runs her husband deteriorates.

∆

Times passes. When I meet my sister two months later, her husband has died. She says, ‘our time together was cut short; there was much more of this to do’. She gracefully gestures at the space between us; the drinks on the table, the words in the air.

∆

One night my partner and I are sat watching TV on our sofa. The night before, we miscarried our first pregnancy. As we sit together, considering what went wrong, what we could have done better, our forearms touch, for the longest time. I think of a speculative third body connecting us, a child, who could lie here between us, linking us, living in the space between us. At night my love traces the speculative names of the child we wish to raise together on my bare back. I think of missed imagined times: the age the child would be now, the act of saying their name, holding their body. I’m infatuated by these parallel lives.

∆

I had an idea that I might name each section of this text after parts of a body, speaking to a bible quote from Corinthians, which I read the other day. It says, ‘The body does not consist of one member but of many […] If the foot would say because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body, that would not make it any less a part of the body.’ But I can’t make this titling idea fit. I like the image of body parts independently chatting away, like a scene from Jim Henson’s Labyrinth.

∆

Rearranging this text, inserting/deleting notes, I change the format, in the drop-down menu from ‘Head’ to ‘Body’.

∆

I think of the hole in Rodin’s sculpture of a bathrobe, where the neck should be; it’s not that the head was cut away, it was never there. I imagine myself climbing inside the glass vitrine in the gallery, which is a bit like a sarcophagus. I’d be hunched over in there, trapped with that sculpture, a headless plaster form. In the airless confines of the vitrine, I imagine it hot and sweaty, like the heat solidifying plaster gives off. But this plaster would be bone dry and aged inside that glass. I would be putting the moisture back. I would put my arms around the object’s shoulders and lean in. The glass of the vitrine would steam up. My wife would have wandered off to another gallery. People would gather around the vitrine and watch.

Jamie George is an artist and writer based in London. He has Art degrees from Goldsmiths, the Slade, and the Cambridge School of Art, and has been the recipient of a Gasworks International Fellowship, Cocheme Fellowship and Jerwood Arts artist bursary.