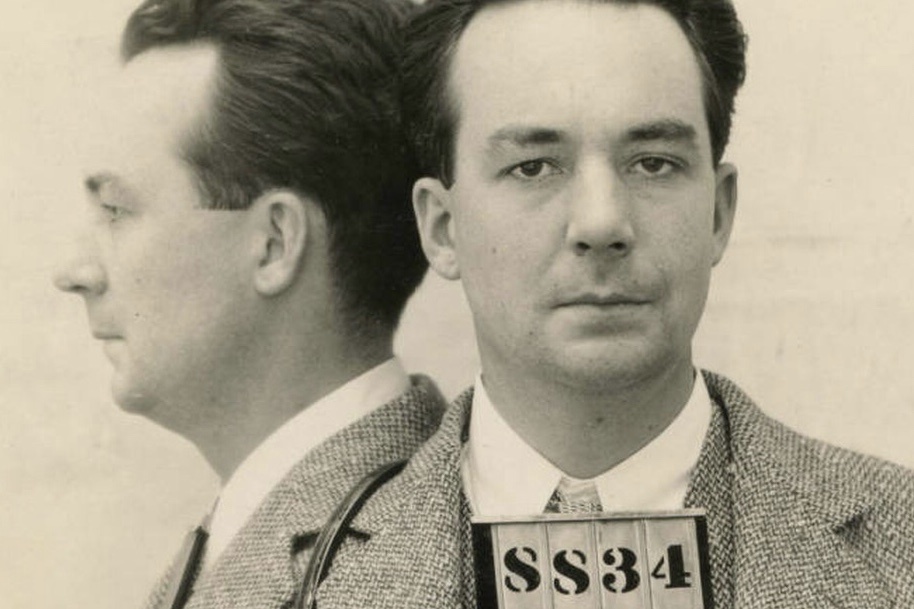

My husband, Richard Elman, was a writer who died in 1997. Less than a year after his death, I received an email from a Canadian woman who had just finished reading Richard’s novel An Education In Blood (1971), which had been inspired by the Lamson case of 1933 in which David Lamson had been charged with the murder of his wife, Allene. The story that became part of the police record was that Lamson had been burning leaves in his backyard on a hot Memorial Day morning when a realtor came to his front door with a client interested in renting Lamson’s house for the summer. With the intent of opening the front door for the women, Lamson entered his house through the unlocked back door. When Lamson opened the front door for the realtor his shirt was covered with blood. ‘My God, my wife has been murdered,’ he cried. Lamson had just found Allene naked in the bath tub with her head bashed in.

The opening pages of Richard’s fiction, An Education In Blood, has the character based on Lamson describing what he remembers of that day in a letter:

…I remember blood, Judith’s, a great pool thickening against the floor as in a shallow basin. The tiny octagonal floor tiles slanting ever so slightly toward the base of the old crow-footed yellow tub. Each tile hiding flecks of blood.

Because my wife and I had not slept together on the night of the ‘accident,’ I was found guilty of murder in the first degree.

Because our former nursemaid proved to be ‘in trouble’ (and later she gave birth to a lovely red-haired son, though my own hair, until fairly recently, was always darkest brunet) the sheriffs believed they had a motive for my guilt.

Judging from Richard’s novel it seemed to Marie, the Canadian woman who had written to me, that the Lamson character was guilty. Marie had her own reasons for believing David Lamson was guilty of murder, and she wanted to know for certain what Richard thought. Did I know if Richard had, in fact, believed in Lamson’s guilt?

In the real world, David Lamson, a sales manager for Stanford University Press, had been sentenced to death, serving thirteen months on death row before winning an appeal to the California Supreme court.

Lamson’s story was that the night before Allene’s murder they slept apart because his wife was not feeling well. Around 3 or 4 AM, she called out to him, and he made her a cheese sandwich and a cup of tomato soup and went back to bed in the other room. At 6 AM, he rose and left the house to do yard work. At 9 AM he returned to the house, woke his wife, brought her a bowl of shredded wheat cereal, drew a bath for her, helped her into the tub, and left her to tend to the small backyard bonfire. He chatted with neighbors, and just before 10 AM he returned through the back door to let in the realtor and her client and discovered his wife’s bloody body draped over the side of the tub.

The prosecutor argued that Lamson was having extramarital affairs, and that his jealous and angry wife suspected. On the night of her death, he proposed that Allene refused to have sex with her husband, using menstruation as an excuse; when Lamson found a pristine sanitary napkin in the bathroom, he knew she was lying. They quarreled and he struck her with a nine inch pipe, later found in the yard bonfire.

The prosecutor insinuated that Lamson had impregnated the unmarried nanny who cared for the Lamson’s two-year-old daughter.

Another paramour of Lamson’s was the divorcee Sara Kelly, who attempted to visit Lamson in jail soon after he was arrested. Lamson had sent Kelly flowers and had been seen with her at restaurants and at her apartment. Two love poems written by Kelly to Lamson were hidden away in his desk. She wrote:

‘If in the days before we meet again/ There shall come into your heart a question/ Any vestige of a doubt that I am yours, ….’

Lamson’s lawyer argued that these poems were creative writing exercises, because Kelly had written across the bottom of the page: ‘Lousy, but you get the idea. Changed rhythm in mid-passage.’ Curiously, neither the prosecutor nor the defense called Sara Kelly to the witness stand to speak for herself.

In his closing statement, the prosecutor held up the iron pipe, banging it loudly as he accused Lamson, though the pipe was never officially admitted as the murder weapon. Reading from the murder scene in Oliver Twist, the prosecutor used Dickens’ words to describe Allene’s murder: ‘She staggered and fell: nearly blinded with the blood that rained down from a deep gash in her forehead.’

The jury deliberated for five hours and came out with a verdict of guilty. Lamson was sentenced to hang on December 15, 1933, and spent thirteen months on death row.

But he won an appeal. The California Supreme Court granted Lamson a retrial on a number of grounds, including jury misconduct — one juror hid that he was a deputy sheriff; another said she was threatened by the foreman when she voted for acquittal on the first ballot. Even more importantly, the Court said the prosecution had not proven that a crime had been committed; the circumstantial evidence was ‘compatible with innocence’ as well as a ‘hypothesis of guilt.’ There was no proof that Lamson had tried to hide his bloody clothes or the body of his wife, and no sign of a struggle. Though Lamson may be guilty, one Justice said, ‘It is better that a guilty man escape than to condemn to death one who may be innocent.’

By California law a unanimous guilty verdict was necessary for Lamson to return to death row, but in two full jury trials that followed, the jurors were consistently split with nine voting to convict and three to acquit. A further trial between the two was called a mistrial and never got off the ground.

Though Lamson first believed his wife had been murdered, he soon changed his mind. Expert testimony was admitted in the second trial to argue that Allene’s death could have been the consequence of an accidental fall; to bolster that defense, a previous resident of the Lamson home testified that his sister had slipped in the very same tub, hitting her head with a ‘hard blow’ – though she had survived the fall.

In the third trial, the undertaker admitted that police officers had paraded in and out of the Lamson home, disrupting the crime scene and making it impossible to tell whose bloody footprints were whose. Three jurors could not convict beyond a reasonable doubt.

Lamson was set free three years after his arrest. He moved to Hollywood to write the screenplay for his nonfiction book about his experience on death row, We Who Are About to Die, and remained a free man for the rest of his life.

‘I don’t know if Richard believed Lamson was guilty,’ I told Marie. ‘We never discussed it.’ I had met Richard four years after his novel An Education in Blood was published. And since Lamson had died in 1976, I wasn’t sure why it mattered now, more than twenty years after his death from natural causes.

Marie explained that the murder of his wife Allene had not been the first death in which Lamson had been implicated. As an adolescent in Canada where he grew up, Lamson had shot and killed his best friend, Dick Sharp, though the death had been considered an accident. Dick Sharp, Marie told me, had been the boyfriend of Marie’s Aunt Rebecca. And according to Marie, Lamson had, at another time, taken a shot at Rebecca, which he’d also claimed to be an accident.

Jealousy, according to Marie, had been Lamson’s motive. Marie believed that the hunting ‘accident’ that had killed Dick Sharp had been no accident. Lamson had been jealous of Dick Sharp – jealous that he had a girlfriend, but more importantly, jealous of Dick Sharp’s loving relationship with his father who was devoted to his son and also kind to Lamson, his son’s friend. Lamson’s own father, Marie contended, had been a morose and angry man. Lamson, she believed, very much desired to have a father like Sharp’s, and she surmised that he had killed his friend with the deluded hope of taking his place in the loving affections of his friend’s father.

Could Richard have known about the ‘accidental’ death of Dick Sharp? There was an urgency in Marie’s desire to find out what Richard knew and thought about the death of Dick Sharp and the death of Lamson’s wife, Allene. In the solitary loneliness of my new widowhood, I felt a special bond with Marie. Though our motives were different, we both missed Richard intensely and desired to talk to him.

I dove into Richard’s writing to unearth what he knew and felt about Lamson, and was excited to share an essay by Richard, ‘David Lamson’, that had been recently published in Richard’s memoir, Namedropping: Mostly Literary Memoirs. In it, Richard said he knew about the boyhood shooting of Lamson’s best friend; Lamson had even written a novel, Whirlpool, based on the incident. But Richard did not make any connection between this boyhood ‘accidental’ killing and the accusations against Lamson for the murder of his wife.

Rather, to insinuate doubt about Lamson’s innocence, Richard turned to another piece of writing by Lamson: We Who Are About to Die, a nonfiction work which Lamson wrote about his thirteen-month experience of death row at San Quentin. Richard noted:

I have no personal knowledge that Lamson was anything but an innocent man, cruelly deprived of his liberty by hasty official judgments but I have often wondered, if he had not been guilty, could he have written so carefully and well about prison in We Who Are About to Die?

The allegations against Lamson were that in a moment of rage he had struck out against his wife who was in the tub and brought about her fatal injuries. Such moments of rage have occurred all too often with husbands and wives. We’re probably all capable of such rages, and afterwards there is remorse, which often takes the form of a heightened awareness of the ordeals of others.

This ‘heightened awareness of the ordeals of others’ was on display in We Who Are About to Die, as Richard comments:

What is most striking in this memoir of a man condemned to die for a crime of which he claimed to be innocent is how little attention Lamson gave to the circumstances of his own conviction, not arguing his case but summarizing it briefly, and how much space he devoted to the cases of others, and to prison life among the condemned.

It seemed to me, I told Marie, that Richard was implying that Lamson omitted a detailed story of his own innocence because he was not, in fact, innocent, and the sensitivity Lamson showed in his writing about the humanity of his fellow inmates was due to his remorse, the remorse of a guilty man.

As an afterthought, I wondered if I could corroborate Marie’s original story about her aunt Rebecca being shot at by the adolescent Lamson, and I found it in a newspaper article from the San Jose News for January 8, 1933. Lamson, the:

. . . accidental killer of a young companion in his boyhood, was involved in the near slaying of a Canadian girl a number of years ago. Sheriff William Emig received a letter from a Canadian mother, giving the information that Lamson fired a rifle bullet at her daughter as she stood in the doorway of her home. The letter also informed Sheriff Emig that the body of Dick Sharp, the boy killed with a shotgun by Lamson 17 years ago, lay dead for two days in the brush before Lamson revealed that he had killed him accidentally.

A chill ran down my spine as I read, ‘lay dead for two days in the brush.’ What kind of friend was Lamson to abandon the body of his best friend, especially if the shooting had been accidental? I felt then a visceral certainty that David Lamson had twice gotten away with murder.

∆

Twenty years after Richard’s death and my exchange with Marie, the Lamson case cropped up again. I received a phone call from a friend, asking if I’d read the latest issue of the New Yorker.

‘No.’ I replied. ‘Why?’

‘Wasn’t Yvor Winters a professor of Richard’s at Stanford?’

‘Yes, he studied with him in the 50s.’ Yvor Winters had come to Lamson’s defense in his 1933 murder trial, and it was through Winters that Richard had heard about the case.

‘Well, there was an essay in the New Yorker about Yvor Winters, and a response to the essay this week mentions Richard!’

It did indeed:

… Another novelist worth noting is Richard M. Elman. Elman was one of Winters’s students, in the same group of Stanford Creative Writing Fellows that included Thom Gunn, and was writing mostly poetry in those early days. But, in 1971, he published a novel, An Education in Blood, about the murder trial of David Lamson, a Stanford graduate. In Elman’s book, a Winters-esque figure appears as a major character. Winters himself wrote three fine poems about the case and a summary of the briefs for Lamson’s appeal. Elman makes use of the summary, as well as letters written to him by Winters urging him not to publish the book.

Winters died in 1968, three years before Richard’s novel was published, and in the letters mentioned he urged Richard not to write a work of nonfiction about the case. Richard agreed to give up the nonfiction project. And when his novel based on the case was published, no one, as far as I have been able to tell, reviewed the novel as a thinly veiled dramatization of the Lamson case of 1933.

After some further research I learned that Winters hadn’t actually met Lamson until after he had been arrested for murder. I’d always assumed Winters had been friends with Lamson before the trial, and had come to his friend’s defense because he had prior knowledge of his character. But that wasn’t so. He became involved in Lamson’s case after his wife, the novelist Janet Lewis, was asked to improve the quality of the writing in the legal brief of Lamson’s defense lawyer. Yvor Winters then took over the editing project from his wife, and also produced a lengthy pamphlet, The Case of David Lamson, in which he focused on refuting the circumstantial evidence produced by the prosecutor. Janet Lewis said her husband began to drink heavily when he worked on the defense of Lamson, and Winters’ increased alcohol consumption continued to be a problem from then on. I wondered if Winters drank to quell his anxiety, his fear that by strengthening the arguments in Lamson’s defense, he was aiding a murderer. After all, he didn’t really know the man.

In an autobiographical essay published in Contemporary Authors Richard wrote that An Education in Blood was ‘inspired by but did not slavishly imitate the David Lamson murder case.’

…I did not wish to sit in judgment of Lamson, and whether he killed or did not kill his wife. I was interested in the combination of literary interests and murderous rage. An Education in Blood…was as much about people like myself, I felt, as Lamson.

I met Richard four years after An Education in Blood was published, and I remembered that when, soon after our first meeting, I told Richard I had read his novel, he conveyed surprise that the novel hadn’t frightened me off. ‘Just because you created a character who murdered his wife, doesn’t mean you were a murderer,’ I told him then.

I began to think about Richard’s statement: ‘….An Education in Blood was an exploration of male rage and numbness and amnesia. …It was as much about people like myself, I felt, as Lamson.’ I was no stranger to Richard’s out-sized temper which could match his 6 ft. 4 inch frame. In the beginning of our twenty years of marriage, we argued about my intrusive mother and how to raise our child. His own unhappy childhood, and his father’s making good on his threats to knock him from ‘pillar to post,’ were never far from his mind. When I was pregnant, we argued about whether to circumcise the baby, even though we chose to remain ignorant about the baby’s sex. I would try to resolve this argument by claiming the baby would be a girl, which, thankfully, she was. Another argument I remember was about my father; when he was dying, Richard didn’t want me to take our daughter to the hospital to visit him. Richard would say something provocative, and I’d respond in kind. The problem was he wouldn’t let up. These arguments would go on for days. He’d follow me around the house, shouting or hissing. Once, he spat in my face. I ran out of the house to escape him. I locked myself in the car and he pounded on the hood. Eventually, he went back inside. I followed, and it would be quiet for a few minutes until he started up again. ‘What did you mean when you said….’ Things escalated. Suddenly, I remembered standing in the kitchen with my back to the counter feeling cornered by him; I grabbed a scissors and held it firmly with both hands anchoring it waist-high so the blades were facing towards him. ‘Come on,’ I screamed, daring him to come closer, almost relishing what it would feel like to pierce his gut with the blade. ‘You’re crazy,’ he said, finally, backing away.

Appalled, we sought professional help.

I’d been so busy focusing on Lamson, that I’d completely forgotten about these scenes from our ancient past. Then I saw myself in the kitchen, ready for my menacing husband to impale himself while I held the blades steady.

Alice Elman is the editor of the Complete Poems of Richard Elman (1955-1997) (Junction Press, 2017) and the author of the memoir ‘What We Were Afraid Of’, which appears in Widow’s Words (Rutgers University Press, 2019).